“Another thing” is a series of occasional posts, each presenting a particularly interesting, beautiful or unusual object on display at one of the museums or sites on our tours.

Bronze ingot from the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck, about 1200 BC. On display in the Museum of Underwater Archaeology at Bodrum Castle, Turkey.

This object may look fairly uninteresting, even rather unsightly, at first sight. As a matter of fact, it is of great importance, illustrating a major landmark in the development of maritime archaeology on the one hand, and a hugely important aspect of Mediterranean prehistory on the other. Beyond that, it stands witness to what must have been a devastating and tragic event some 3,200 years ago.

On display in the superb Museum of Underwater Archaeology housed in the medieval castle of St. Peter in Bodrum (Western Turkey), it is a so-called oxhide-shaped copper ingot. It was part of the cargo carried on what is now known as the Cape Gelidonya Shipwreck.

These are household terms for a prehistorian, but quite obscure for anyone else. Time to explain:

Cape Gelidonya is a headland in eastern Lycia, on the southern shore of Turkey; it marks the southwestern extremity of the Bay of Antalya. To all accounts, it is a treacherous place for seafarers. In 1954, a sponge diver from Bodrum, working in the area, came across some unusual objects, such as the one shown. A few years later, he described them to American reporter Peter Throckmorton, who realised this was a significant find, most probably a prehistoric shipwreck. Soon after, in 1960, Gelidonya became the site of the first ever systematic underwater excavation of a shipwreck, supervised by American archaeologist George Bass, then still a student, who subsequently became one of the fathers of nautical archaeology.

The excavation revealed the cargo and a few structural elements of a ship that sunk around 1200 BC, most likely after hitting a rock pinnacle protruding just under the surface of the sea. It was a trading vessel of small size (probably between 10 and 20m, or 32 and 65ft, in length). Its contents indicate that it was plying its trade in the Eastern Mediterranean: they include objects from Greece, Southern Anatolia and Cyprus, but the ship's home port was most likely somewhere on the coast of Syria or Palestine. At the time of the excavation, it was the world's oldest known shipwreck, a place it subsequently lost to the spectacular Ulu Burun Wreck, also off Lycia and also on display in Bodrum and about a century older, outdone more recently by the Dokos Shipwreck, discovered near the Greek island of Hydra and dated to about 2200 BC.

The Gelidonya ship carried a cargo mainly of metal, including a collection of scrap bronze objects to be melted down for reuse, and raw tin and copper in the form of ingots. Our object is just one of 34 copper ingots from the wreck, each about 65cm (40'') in length and weighing about 25 kilograms (55 pounds) - nearly a metric ton of copper!

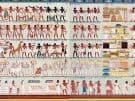

A fresco in the 15th century BC Tomb of Rekhmire (near Thebes in Egypt) shows various foreign peoples bringing tribute. The fellow at the right hand of the sedond row from the top on the left is shown carrying an oxhide ingot and a typically Cretan vase.

The presence of those copper ingots is what made Gelidonya such an important discovery. In the Eastern Mediterranean, the period between roughly 3200 BC and 1150 BC is known as the Bronze Age, so defined because the most versatile and advanced material available for tools and weaponry at the time was bronze (iron metallurgy had yet to be discovered). Especially the Late Bronze Age, after 2000 BC, is an immensely important era in the area, comprising the development of complex societies, the first civilisations, the beginning of writing systems and the rise of the first states and empires in Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Levant, Anatolia, Crete and, eventually, Mainland Greece. Another key factor distinguishing that period is the existence of sustained long-distance trade contacts between those regions.

Those contacts were a necessity. Unlike iron, produced from iron ores, which are quite widespread, bronze is difficult to procure and does not occur naturally. It is an alloy of copper and tin, both of which are not distributed widely in the region. Leaving tin aside, the main source of copper appears to have been Cyprus, perhaps complemented by Attica, Sardinia and other regions. One way or another, the production of the leading material for tools and weapons necessitated stable long-distance contacts.

Oxhide-shaped copper ingots from the Minoan sites of Kato Zakros and Agia Triada on Crete in the museum at Heraklion. (Image: Olaf Tausch)

This was known before the discovery of the Gelidonya wreck, and raw copper in the form of oxhide ingots (they were probably shaped that way to make them easier to carry) had been found at a whole range of important sites, such as Mycenae in Greece, Zakros on Crete and the Hittite capital Hattusha in Central Anatolia. Such ingots were also known from Egyptian depictions of foreign peoples bringing tribute. They must have been immensely important objects to acquire, as they were the source for most tools in the household, warfare and ceremony. Some scholars suggest that copper ingots may even have served as a currency of sorts, long before coinage was invented.

Even though archaeologists already realised that copper must have been traded across the seas, and most likely in the form of the oxhide ingots discovered in small quantities here and there, the discovery of the Gelidonya wreck made that trade tangible for the first time. It became a major trigger for research, pioneering the techniques of underwater archaeology and contributing to the development of archaeometallurgy, the chemical study of ancient metals. One example of that field's results is the secure sourcing of the Gelidonya ingots: they are indeed from Cyprus.

We should be thankful for the existence of the Gelidonya wreck and for the work of those who found and studied it, but we should also keep in mind that the root of this discovery must have been tragedy for those involved in its loss. If you want to learn more about the Mediterranean Bronze Age, you should consider joining us in the Bodrum Museum on our Carian and Aegean cruises, travelling with us on Cruising to the Cyclades, discovering the great Minoan civilisation on Exploring Crete tour, or visiting the Hittite capital Hattusha on Walking and Exploring Cappadocia and the Land of the Hittites.

Leave a Reply