The North Bastion of the 'Palace of Minos' at Knossos, on the one hand a controversial reconstruction, on the other a shorthand for the monumental glamour of Minoan Bronze Age architecture.

Crete, the largest of the Greek islands and a place very close to our heart, has appeared on Peter Sommer Travels' blog before. Of course it has: Exploring Crete, the trip through the island that we've been offering since 2013, has long been among our most popular tours. We have posted about preparing that tour (a long time ago), about individual sites on the itinerary (such as Gournia and Lato), and about some of the wonderful material left behind by the island's Bronze Age 'Minoan' culture (namely its pottery and frescoes).

But we've never written a stand-alone post about quite why Crete as a whole is such a special place, what makes it so distinctive even among the many wonders of Greece, its mainland and islands.

Of course, there's more than one way to do that, more than one reason someone might find Crete special. We could write about the island's amazing natural diversity, with its three distinctive climate zones and its vast array of landscapes, ranging from coastal wetlands via arid hills to mountain terrain with alpine vegetation (this video shows some of it in a rather amusing way). Or we could compose a post about Crete's impressive and profound living traditions: the surprisingly durable way of life, the language and poetry, but most importantly the music and the celebrated Cretan cuisine.

Today, we present another aspect of Crete's uniqueness, its history, for Crete has had three 'Golden Ages'!

Every bit as amazing as the fact that Crete has had three Golden Ages is the fact that there are living olive trees in the island that have seen at least two of them. This one, near the village of Anisaraki in the southwest of Crete, is estimated to be 3,000 years old!

What do we mean by Golden Age? Admittedly, it's not an objective analytic term, nonetheless it's often used. It may be somewhat subjective, but it is quite easily and convincingly defined. I would say it's a period when a city, region or country is not just flourishing in terms of affluence or power, but when it is exerting strong cultural influences beyond its immediate surroundings. It's an era when a civilisation or a people produces cultural achievements that shine and echo across space and time. It's when a place 'punches above its weight' in cultural terms.

Examples? Athens had a well-known Golden Age in the Classical era of the 5th century BC (during the height of its power), when it created many of the cultural achievements we associate with Ancient Greece; Rome had one in the first few centuries AD (when the Roman Empire was stable and immensely influential) and another in the 15th and 16th (when the city was a central hub of Renaissance and Early Baroque advances); London and England had one from the 18th to early 20th centuries when the British Empire and industrialisation, but also British philosophy and literature, bore immense global significance. There are many other examples, some lasting centuries, some just decades (e.g. Berlin in the 1920s). What they all share is a surplus of creativity, and in the way I see it, they're defined by the fact that this creativity still affects us now.

Crete has had no less than three such eras of high cultural impact, each lasting for centuries - and most visitors are only aware of the first.

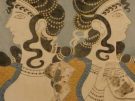

A fresco from the Minoan 'Villa' at Amnisos near Heraklion, depicting an illusionist architecture with lilies growing from a flowerpot. The same room also had images of mint, iris and papyrus plants. Circa 1550 BC, Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

1. The Late Bronze Age - 'Minoan' civilisation

In the late Bronze Age, between about 1900 BC and 1450 BC, Crete was a cultural beacon!

How so?

The island was affluent, the dominant cultural force, perhaps also the dominant political force, in the Aegean region. Before that period, the Cycladic Islands in the central Aegean Sea bore that role, and after the 15th century BC, dominance had passed to the 'Mycenaean' mainland. But during those roughly four centuries, Crete was exceptional. It's the era we call 'Minoan'.

Crete had formed the first example of what we might call a state outside the Middle East and Egypt (with whom it was in contact), nearly four millennia ago. Internally on the island, this meant a functioning bureaucracy recording the island's economic transactions, a written language (that we still can't read) to enable such record-keeping, a set of monumental architectural complexes (we now call them 'palaces') as venues for that system, and much more, all strongly implying a lasting political structure of some sort. Externally, Crete maintained an apparently stable network of wide-ranging trade connections, some even believe that its fleet ruled the waters of the Aegean. This system was stable enough to survive a major catastrophe around 1700 BC, when all its palatial centres were destroyed and immediately rebuilt. Its affluence led to an immense explosion of specialised craftsmanship and artistic creativity, in the forms of decorated pottery, small-scale sculpture, monumental architecture, wall-paintings (a new art at the time), metalwork and more. The Bronze Age Cretans (whom we conventionally call 'Minoans', although we don't know what they called themselves) produced many things of great beauty, a vast repository of fascinating imagery, much of which remains quite mysterious. In turn, their creativity influenced the Mycenaean culture of the Greek mainland. Moreover, the rediscovery of Minoan art in the early 20th century caused great excitement and revived its influence, now on the era's contemporary style, Art Deco.

Alabaster rhyton (ritual vessel) in the shape of the head of a lioness. From the Palace of Knossos, 15th century BC. Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

The heritage of Minoan Crete can be seen all over Crete and beyond. There are fantastic, beautiful and evocative sites to be beheld in the island, such as the Palaces at Knossos, Phaistos and several other places, the Minoan towns at those and at many more locations, also the cave shrines and mountain peak sanctuaries, and the Bronze Age cemeteries across the island. The archaeological museums of Crete display an amazing wealth of artefacts reflecting the Minoan achievement, its boundless creativity and bafflingly timeless aesthetics. Their further influence can be seen in sites and museums all over Greece, from the famous Bronze Age settlement of Akrotiri on Santorini to the treasures of Mycenae in the National Museum of Athens.

The so-called Gortyn Law Code, one of the longest inscriptions to survive from ancient Greece. Written in the boustrophedon system (with the direction of writing alternating between left-to-right and vice versa) and in Doric Greek, it records not a law code, but amendments to one, dealing with various matters, such as inheritance, marriage rights, adoption, punishment for rape. The inscription itself is dated to the early 5th century BC, but some scholars believe that its content is older than that.

2. The Late Iron Age and Early Archaic era: resurgent art and state formation

In the Late Iron Age and Early Archaic periods, the 8th to 7th centuries BC, Crete was pioneering!

In what sense?

The Bronze Age civilisation, then centred on the Mycenaean mainland, had collapsed in 12th century BC (for reasons that are still unclear). Along with most of the Eastern Mediterranean, Greece, mainland and islands, had fallen back into a more local existence, with limited external connections, simpler craftsmanship and art, no writing and much less social or political organisation: a tribal lifestyle. Only gradually were connections re-established, and only slowly did societies reorganise, eventually to form the phenomenon we know as the polis or Greek city-state, a network of constituted entities that was to become the basis of the great achievements we now recognise as 'Ancient Greece', including its literature, philosophy, science, art and so on.

A remarkable offering found in the Idaean Cave, legendary birthplace of Zeus himself. Dated to about 700 BC, it is a large bronze shield or cymbal with repoussé decoration. The figure in the middle, stomping a bull and tearing a lion, is probably Zeus. He is flanked by two winged male figures holding drums, shields or cymbals. These are most likely the kouretes, magical Cretan warriors that beat their shields to make sure Zeus's vengeful father Kronos could not hear the infant god. Altogether, this might depict some earlier or garbled version of that tale, as Zeus is hardly a baby here. The animal wrestling is not a typical attribute of Zeus, but of various Middle Eastern deities. The image style, the wings on the kouretes and the technique all suggest Middle Eastern craftsmanship, underlining Crete's early re-establishment of long-distance links. Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

While we nowadays associate these achievements especially with Athens, also with southern mainland Greece, the Ionian coast of Anatolia and of course Greater Greece (Sicily), Crete appears to have been an early leader, likely due to the island's geographic location between Europe, the Middle East and Africa (especially Egypt), placing it next to various maritime routes. Specifically, Crete developed the "Daedalic" style of elaborate sculpture in stone, bronze and other materials, which thrived throughout the 8th century BC, placing Crete ahead of the rest of Greece by up to a century and eventually exerting an influence on Early Archaic Greek sculpture. Less tangibly, Crete also appears to have had a leading role in the development of the city-state. Homer, probably writing around 700 BC, describes the island as "of the hundred cities". A few centuries later, Aristotle (384-322 BC) credited the Cretans with having formulated the first city-state constitutions in the island itself, before advising the rest of Greece on such matters.

Although Crete had lost its pioneering position by the 6th century BC, there is plenty of evidence to be seen. At Eleutherna Museum, the rich contents of 8th and 7th century tombs illustrate a society in transition from tribe to state. The web of city-states established by the 7th century proved remarkably durable, with most of Homer's 'hundred cities' surviving until the Roman era and the remains of many of them can be visited, such as Gortyn, Aptera, Lato or Eleutherna and in some cases, inscriptions referring to their political organisation survive. The Daedalic style of sculpture can be admired in the island's archaeological museums, most importantly at Heraklion. Its echoes are also present at many major archaeological sites across the rest of Greece, especially at sacred places like Delphi, Olympia or the Heraion of Samos.

The southern aisle of the church of the Panagia (Virgin) Kera near Kritsa in East Crete, is dedicated to Agia Anna (St Anne), the mother of Mary. Its rich fresco decoration, depicting events from the lives of mother and daughter, is from the early 14th century.

3. Crete's Venetian era: maintaining and transforming the Byzantine tradition

As the great empire of Byzantium faded and eventually fell, Crete became a central conduit of its art and culture!

What happened?

The eastern part of the Roman Empire, centred on Constantinople (modern Istanbul) and nowadays usually called the Byzantine Empire, survived the western part by nearly a millennium, until 1453. During that long period, it developed its own distinctive culture, a blend of Roman and Greek elements in a Christian context, and in many ways a bridge between the traditions of antiquity and the Early Modern era. During its last few centuries, the Byzantine Empire was increasingly beset by internal social and economic crisis, making it vulnerable to attacks and disasters. The greatest of those was the Sack of Constantinople by westerners during the Fourth Crusade in 1204. In its aftermath, western powers divided up the erstwhile Byzantine territories, including Venice acquiring Crete.

Christ Pantokrator (the Almighty) enthroned. Cretan School icon of the late 14th or early 15th century. Historical Museum, Heraklion.

The first two centuries of Venetian Crete were dominated by instability and strife in the island, with constant conflict between Venetian (Roman Catholic) settlers and the Cretan (Orthodox) natives, both also repeatedly rebelling against Venice herself. Eventually, a system of coexistence, even integration, was established, leading to an era of prosperity in the 15th and early 16th centuries that lasted until the Ottoman conquest of the island, completed with the end of the 21-year Siege of Candia in 1669. But even before the 15th century, Venetian Crete had started to become a refuge of Byzantine tradition and culture, ever more so as Constantinople gradually weakened and finally fell. Thus, Crete became a cultural hub, an interface between Eastern and Western culture and art.

This flourishing has left behind a rich heritage in two forms. The first is the extraordinary wealth of painted churches in the island: there are several hundred of them, ranging across several centuries and different levels of sophistication, from first-rate quality indicating direct connections with Constantinople to more provincial efforts. Of course, we visit some key examples on our tour of the island. The second lasting legacy of the era are the icons of what is known as the 'Cretan School', created by Cretan artists in the Byzantine tradition, together with others arriving from erstwhile Byzantine lands. They continued to develop the Byzantine artistic style, selectively adopting western influences. This final flourish of Byzantine art lasted from the late 14th to the 17th century and gave rise to many well-known painters, none more famous than Domenikos Theotokopoulos (1541-1614), better known as El Greco. Since icons are portable objects, we see works of the Cretan School not just in monasteries and churches during our tour of Crete, but also in the Cyclades, the Greek mainland (south and north) and much further afield, for example in the former Venetian cities on Croatia's Dalmatian Coast.

Mt Sinai and the Monastery of Saint Catherine, by El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos). It was painted around 1570, a few years after Theotokopoulos had left Crete for Italy. He moved on to Spain in 1577. Historical Museum of Crete, Heraklion.

---

One island, three Golden Ages - that's Crete!

Crete, albeit the largest of the Greek islands, is a well-defined place of limited size, just 255km (158mi) long from west to east and 55km (34mi) from north to south at its greatest width. An unbelievable amount of archaeological and historical sites is concentrated within that area, including sites associated with the three periods listed above, but of course also with much more of Cretan history, from the Palaeolithic via the Classical and Roman era to the Ottoman period, the Second World War and beyond...

Come and discover the great island and its many stories with our expert guides on our Exploring Crete tour!

Leave a Reply