Well, maybe not quite. This is indeed an ancient Greek inscription, dating to about 300 BC and on display in the small epigraphic collection at the Asklepieion of Kos.

The what of what? The Asklepieion on the island of Kos was one of antiquity's most celebrated sanctuaries of Asklepios, the god of healing, a place that attracted visitors in their thousands, seeking help with physical ailments. It is a central part of our visits to that island on Cruising to the Cyclades, Cruising the Dodecanese and Cruising the Southeast Aegean: an enchanting site set on a series of terraces overlooking Kos Town, the East Aegean and the shores of Asia Minor. Epigraphy is simply the study of ancient inscriptions.

Another inscription from the Asklepieion, also from about 300 BC. This one records a sacred law forbidding the felling of cypress trees within the sacred grove.

Inscriptions are a fantastically important source of information on life, belief and politics and the practicalities of all those things in ancient Greece and Rome. Our understanding of antiquity relies primarily on three pillars. One is archaeology proper, the study of material remains such as buildings and artefacts. It tells us much about daily life and public life, economy and art, but it has limitations due to its relatively accidental preservation and the “muteness” of its subject matter. The second is history, the study of written records of what happened in the past. This uses a relatively small body of preserved sources, which are eloquent, but all of which are subject to bias. Epigraphy stands somewhere in between: being direct communication in writing, it is as real as archaeology and as eloquent as history and opens up a vast and fascinating array of detail that would otherwise be entirely inaccessible to us. Often, it elucidates aspects of ancient life that would remain entirely incomprehensible, even invisible, without it.

In an age prior to printing, prior to mass media and way way prior to the internet, inscribing information on stone (or other materials) was an immensely powerful way to communicate information, to disseminate it to the viewer/reader and to preserve it – in the latter regard it may be superior to much of what we do now (who knows how long this blog post will be accessible to readers?).

Also from the Asklepieion, this inscription simply naming "Athana Fatria" is probably dedicated to what conventional ancient Greek (Ionic Greek in other words) would call "Athena Phratria". It identifies a space sacred to Athena as the patroness of tribes, i.e. clan-like units within the city-state. Athana is the Doric version of Athena, and the people of Kos were Doric Greeks, speaking and writing that distinctive dialect.

Ancient Greek (and Roman) inscriptions come in fairly few forms, but can communicate a range of topics. Typical ones include boundary markers (“you are now in the shrine of god A”), official decrees (“law or measure B has been passed”, followed by much detail), treaties between city states (“city C and city D have agreed on E”, also usually detailed), grave markers (“here lies F, son of G, from H”, sometimes with additional thoughts, often poetry), votive inscriptions (“J dedicated this statue/building/object to deity K”) and honours (“city L decided to put up this monument in gratitude to individual M”, usually listing the beneficiary's achievements). All of them aim to make their content permanently visible and legible. And all of them communicate relevant information, primarily relevant to the intended viewer, i.e. the literate citizen of the city in question, potentially for a few generations down the line, but also now relevant to scholarship. Inscriptions on vases ("N is beautiful") and graffiti ("O did P-Y to Z") are a different category, admittedly.

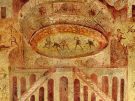

Our example from Kos is very revealing. It is about the worship of the nymphs, local chthonic (earthbound) deities that were revered all over the Greek world as nature spirits, associated with springs, rocks, caves, trees and such. They were popular deities and apparently they were worshipped by the visitors to the grand shrine of Asklepios alongside other gods, and apparently that was a problem.

Our inscription states that sacrifices to the nymphs are to be made only on the altar dedicated to them and not elsewhere. More specifically, it stresses that sweets and other offerings to the nymphs are not to be deposited in the springs and wells of the sanctuary.

The waterspout of one of the fountains in the Asklepieion is actually decorated with a relief of Pan, the goat-legged god of herds, playing the pan pipes and sitting in a stylised cave. Pan is the patron of nymphs and likewise of fountains!

In a few lines, this text tells us a true and very real story of ancient life: it indicates that people were in the habit of sacrificing offerings to the nymphs by tossing them into the sanctuary's water sources, much as people throw coins into wells today. This habit would have created practical and perhaps also hygienic problems, so it was discouraged. Eventually, the problem became so severe that it had to be stopped formally and a suitable alternative was provided: an altar for the nymphs and a ban on sacrificing to them anywhere else – a practical solution to a problem arising from a spiritual belief and the physical results to which it led.

So, a very short text throws light on multiple aspects of ancient Kos: on the presence and practice of the cult of the nymphs within a shrine to Asklepios, on the nature of the offerings made to them (sweets), and on the need to regulate the unruly. It makes it easier for us to understand the sometimes chaotic realities of such places, and brings us a step closer to imagining their life and lives.

Inscriptions can do much more than that. You can see this one, along with others that illustrate other aspects of the Asklepieion, on our tours visiting Kos, such as Cruising the Dodecanese. And you can see others on virtually all of our escorted tours in Europe.

Leave a Reply