A panoramic view of Limenas, ancient Thasos, as seen from the sanctuary of Athena, by the city walls high above the centre.

I was on Thasos a few weeks ago (for the first time in a while), and it struck me just what an extraordinary place it is! Thasos (sometimes spelt Thassos) is a lesser-known Greek Island and Limenas is its capital town. The island is a smallish one, set in the North Aegean, just off the coast of Eastern Macedonia. With its verdant forested interior and multiple lovely sandy beaches, it has long been an attractive destination for visitors from all over Europe. Since the island has no airport, virtually all of them first set foot in the small town of Limenas, where all ferries arrive. Few of these visitors realise that they are stepping into an enormously important archaeological site the moment they enter the island.

How so? At first sight, Limenas looks like another typical modern Greek island port town, charming but not spectacular. A closer look, however, reveals that the smallish settlement is rattling around within the remains of a much larger and very ancient city: walking through Limenas, one happens upon the ruins of that city every few steps.

A wealthy colony

A detail of the enormous marble quarries at Aliki, in the southeast of the island.

The ancient city was called Thasos, like the island, and it was founded around 680 BC by settlers from Paros, another Greek island located much further south, namely in the Cyclades. It is now impossible to assess what made Parian settlers choose Thasos, but it is striking that both islands ended up thriving from the same rare resource: high-quality marble (both islands still produce marble; Thasos is Greece's main source of it nowadays). Several centuries later, around 384 BC, the Parians participated in colonising an Adriatic island, Pharos (now called Hvar) on the Dalmatian coast of modern Croatia, also famous for its quarries of marble-like stone. Thus, either the Parians chose to colonise islands with high-quality stone in the first place, or it was natural for them to explore such resources wherever they settled. Their Thasian descendants certainly performed successfully in this regard: the site of Aliki in the southeast of the island is one of the most significant marble quarries in the Aegean, exporting stone from the Archaic era of the sixth century BC for over 1,000 years.

The key features of a Greek city

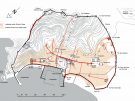

A plan of ancient Thasos town, with its walls, gates, shrines and public buildings (labelled in German). By Gerhard Haubold [CC BY-SA 3.0 DE (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)].

Be that as it may, Limenas is a wonderful place to visit, because it reveals one of the best-preserved ancient Greek cities, extensively excavated and unusually approachable. If you want to understand how a sizeable Greek city functioned, and how its various features were arranged, Thasos/Limenas is on a par with a very short list of places, such as Priene in modern Turkey, Kos in the Dodecanese, Samos in the Eastern Aegean or Morgantina on Sicily. In Thasos, nearly all the physical elements of the city-state are present, and all are executed in especially fine fashion. Looking at their geographic context, maybe the Thasians felt a need to underline their identity: after all, their island was set close to the shores of the Macedonians, who followed a somewhat different trajectory within Greek state formation, and also close to the shores of the Thracians, a 'barbarian' (non-Greek) people.

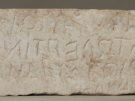

Detail of an inscription from the agora, recording a law against renegades, late 5th century BC. Thasos Archaeological Museum.

The Greek city state, its functions and features, is a central topic our experts explain and discuss on most of our tours in Greece and Turkey. What are the typical features of a Greek city-state? In abstract terms, it is a community based on some kind of formal constitution (not necessarily democratic), designed to regulate how people live together, how conflicts are settled and how decisions are made. In physical terms, it tends to include a series of features that define the city's life and identity and that would be beyond the reach of an individual, a household, a clan or even a village. These include common defences surrounding the town (city walls), defined residential areas (housing), various types of civil engineering (water supply, drainage) and infrastructure (roads, harbours), monumental structures for worship (shrines, temples), venues for entertainment (theatres, displays of artwork etc) and athletics (gymnasia), facilities for commerce (markets), as well as for administration, government and various forms of public display (an agora and associated structures), and finally areas outside the city proper, designated for the disposal of the dead (necropoleis). An additional type of evidence can be constituted by inscriptions documenting various aspects of that urban life.

It is common enough for some of these elements to survive as physical and tangible evidence for the life of the ancient city, but rare for virtually all of them to do so. That's what makes Thasos/Limenas such a wonderful place to explore.

The city walls

A stretch of the city wall in the southwestern section.

Limenas is surrounded by one of the best-preserved circuits of ancient city walls in Greece, built originally before 500 BC, but restored and rebuilt on many occasions (Thasos was twice forced to demolish its walls: in 491 BC by the Persians and in 463 BC by the Athenians. In both cases, a major power attempted to eliminate the danger of Thasos being used as a stronghold by its opponents). With a total length of over 3.6 kilometres (2.24 miles), they ran along the seafront and through the small coastal plain that is now occupied by the modern town, then curving steeply upslope to gain the crest of the hills behind town, up to a height of 155m (510ft) above sea level, denying any attacker the nearby high ground, before returning to the plain.

The Gate of Silenus, one of the best-preserved along the walls of Thasos. Note the large relief of the mythical character, Silenus, on the left-hand side. The wall in the right foreground belongs to a tower.

These walls are a reflection of how affluent Thasos must have been at the time. They are exceptionally well built. At a time when even great cities like Athens had city walls of mostly mud-brick on a stone foundation, those of Thasos were constructed largely of stone, namely a foundation of local gneiss with a superstructure of marble (of course!), forming an outer and an inner face (the space between was filled with rubble, stones and soil). On the slopes, they were about 2m (6.6ft) thick, in the plain about 3m (10 ft). The substantial use of stone is why nearly their entirety survives and can be walked along, from stretches bathing in sunlight between the gardens of the outer parts of Limenas, to others perched precariously on the steep slopes and cliffs above town. Although the walls do not survive to their full height (estimated at 8 to over 10m, or 26 to over 33 ft) in any location, they are a key example of Ancient Greek fortification architecture.

The relief on the gate of Silenus, from c. 500 BC. It shows horse-tailed Silenus, member of the entourage of Dionysos, the god of wine, striding towards the city. He is holding a kantharos, a wine-drinking-cup that appears full. Although there appears to have been an attempt to censor the relief (2.5m/8ft tall) at some point, it is still clear that Silenus is looking forward to his visit with considerable enthusiasm.

The walls of Thasos were a complex defensive system, with over a dozen stairways giving access to the now-lost wallwalk, at least 22 towers (up to 15m or 50ft in height) and twelve gates, permitting movement between the city, its agricultural hinterland and the rest of the island. Especially the gates are fascinating. Some are purely functional, simple and narrow openings in the wall (posterns), while others feature towers or other defensive measures. In the flat area where the town centre and most of its residential areas stood, many gates have ostentatious marble orthostats (uprights) that bear carvings of gods or mythological figures, thus the names given to them by the (French) archaeologists who explored the site: Gate of Zeus and Hera, Gate of Hermes, Gate of Silenus, Gate of the Goddess in a Chariot, and so on. It is quite compelling to imagine that they bore similar names in antiquity, and they are an interesting reflection of how Greek polytheist religion permeated all aspects of city life.

There are many fascinating details to be observed along the walls: varying building techniques, details of defensive architecture, mason's marks and much more. One of the most delightful is a small inscription near the southeastern corner, stating Parmenon epoiesen (Parmenon made it). We don't know who this Parmenon was, but in all likelihood we're looking at the 'signature' of an architect or maybe a contractor.

Houses, streets and urban planning

A lane flanked by the foundations of private homes, near the gate of Hermes.

Excavations have revealed considerable stretches of the streets of Thasos. We can distinguish between major and minor streets (or lanes), centered on a wide central avenue linking the agora with various sanctuaries in the heart of the city. A long paved path runs from the centre through a ravine up to the height of the city walls. There also appears to have been a street running alongside the walls on their interior side. The major streets were paved in stone.

Thasos did not have a fully rectilinear street grid, as featured in cities like Miletus, Priene, Piraeus, Olynthos and many others. This is no surprise, because rigid plans became common relatively late, by the late fifth century, when Thasos was already an old settlement. That said, at least the lower part of the city does appear to follow a rough version of such a grid, judging from the layout of the visible streets.

Foundations of private homes inside the Gate of Silenus.

There are better places than Limenas to study the private homes of Archaic and Classical Greece, the best being Priene (Turkey), Olynthos and Stageira (both part of our Exploring Macedonia tour in Greece), Kassopi and Orraon in Epirus (western mainland Greece), Athens (with difficulty) and a few more. But Thasos has some approachable examples of house foundations, especially inside the Gate of Hermes and the Gate of Silenus, where we can make out the basic house plans, with homes of roughly similar size made, each made up of small rooms arranged around a small internal courtyard, the thickness of the foundations clearly indicating that these homes were multi-storey structures, with one or two upper floors.

Water supply and drainage

A marble-lined well near the agora.

In many locations, drains can be seen running just underneath the streets and squares of ancient Thasos. These did not just allow waste water to exit the city (a very important function), they also served as storm drains: the Aegean region may appear dry and arid to the summertime visitor, but it is prone to very heavy downpours in the autumn and winter and any architecture that is meant to last needs to include provisions for those, to this day. Needless to say, the Ancient Greeks were well aware of this. Especially impressive are the openings that allow water to escape the city underneath the city walls in a number of spots.

The flipside of the same practicality is water supply. In Thasos, this is a problematic topic: the aqueduct systems that are omnipresent in ancient cities are not yet well-understood here. The coastal plain of Limenas is rich in water, and many wells can be seen among the archaeological remains, as the water table was low below the surface.

Harbours

The now-submerged great breakwater of the commercial port.

Thasos had at least two well-built harbours, set side by side and making use of the coastline's natural topography. As an island city-state, founded by dyed-in-the-wool islanders, and as a community thriving on the export of stone, Thasos must have set great store by its ports.

Adjacent to the town centre was the 'closed harbour', thus called because it was enclosed by an extension of the city walls with multiple towers, keeping it safe from enemy attacks. It also included a series of shipsheds on its interior: these were elongated buildings connected to the port by ramps, so that ships could be pulled into them for maintenance. Shipsheds are a typical feature of ancient Greek military harbours.

Adjacent just to the northeast was the more open commercial port, protected from northern winds by a large breakwater that can still be made out below the present surface of the Aegean.

Sanctuaries

Foundations of the Temple of Dionysos, with a small altar visible on the left.

Ancient Greece was a polytheist culture. Apart from the Gods of Olympus, usually said to be twelve in number, who were worshipped by all Greeks, there were countless local divinities, demi-gods, mythological or legendary heroes, and so on. The same applied in Thasos and the evidence for the role of Greek religion in the city is second to none, as multiple separate sanctuaries to individual deities have been identified scattered throughout the city, along its walls and even outside their confines.

A typical Greek sanctuary is an enclosed area or precinct, containing one or several altars (this is the minimum definition of a sacred place), a shrine or temple, i.e. a building serving as the house for the image of the deity, and sometimes various ancillary structures. A sanctuary is virtually always defined and set apart from other areas and can be dedicated to one or several deities. Thasos has a staggering number of them.

The sanctuary of Apollo on the highest point of the city walls (now a Genoese fort) as seen from the Temple of Athena.

Within the city centre, there were precincts dedicated to Zeus, father of the gods (in the agora), to his son Herakles (Hercules), the all-popular demi-god and hero respected by all Greeks; to Artemis, the virgin huntress and twin sister of Apollo; to Dionysos, the god of wine and theatre; as well as - near the port - to Poseidon, older brother of Zeus and god of the sea. Additionally, a number of the gates near the centre may have served as shrines to some extent, as can be suggested for that of Zeus and Hera or that of Hermes.

Further shrines were located outside the centre. Two major sanctuaries stood inside the walls high above the city: that of Apollo, god of light and order, at the highest point of the defences (modified by a much later fort, constructed by the Genoese during the Middle Ages) and that of Athena, goddess of wisdom and urban governance, occupying a large artificial terrace that once held a temple towering high above the city and overlooking it. Also near the upper walls is the rock-cut pseudo-cave sanctuary of Pan, that mysterious nature-god, his likeness carved into the rock above the hollow that was meant to receive sacrifices. On a headland just outside the city walls was the Thesmophorion, a shrine to Demeter and her daughter Kore/Persephone, whose story we have told you elsewhere.

The religious changes that affected the Greek World during the later Roman era are also visible at Limenas: several Early Christian basilicas are visible among the remains.

Entertainment

The theatre, high above the ancient city.

No Greek city worth its salt could exist without a theatre and indeed, Thasos features a fine example, set just inside the walls on the slopes east of the city, where it was placed in a natural hollow of the terrain. Thasos already had a theatre in the fifth century BC, but the structure now visible dates from the fourth, with many later modifications. Its auditorium or koilon had seats for at least 3,000 spectators. It served as the venue for the performance of dramas, most likely in the context of the cult of Dionysos. Currently, the monument is being restored, so that it can be used once again.

In the heart of town, next to the agora, there is a second, much smaller theatre-like structure. Dating from the Roman era, the second century AD, this is probably to be interpreted as an odeion, a structure for the performance of concerts, perhaps also for meetings, conferences and the like.

Athletics

The base for the monument of Theogenes in the agora. In his description of Olympia, Pausanias tells its peculiar story.

Well, there is a reason why I wrote that nearly all major aspects of the ancient city are visible at Limenas. We take it for granted that athletics played an important role in the lives of young males in every Greek city-state, and there is copious indirect evidence in Thasos as well. Inscriptions refer to the office of gymnasiarch, the civil servant responsible for the maintenance and running of a gymnasium.

Further, one of the most famous Thasians was a certain Theogenes, a boxer, wrestler and runner said to have won 1,400 victories at athletic contests all over Greece, including the 480 BC Olympic Games. Considering him a hero after his death, the Thasians set up a bronze statue for him in the agora.

Still, the archaeological exploration of the city has so far not revealed the location of any of the structures we should expect in this context: no gymnasium or palaistra (buildings dedicated to athletic training) is known so far, nor has a stadium been located. Who knows - maybe the future will reveal them?

The agora: commemoration, administration and commerce

A view across the agora of ancient Thasos.

The term agora is often translated simply as 'market', but that falls short of describing the multiple functions this space, a central feature of any Greek city, served. They included commerce, but also government, religion, law and, most important of all, public representation. The agora, an open area of variable shape and dimensions, was the heart of a Greek city-state and the place where all aspects of communality took place, were performed and commemorated. Thus, an agora tends to be surrounded by impressive and monumental public buildings and to contain statues, inscriptions and other such items, a visual expression of the city's very identity, its history, mythology etc. Our tours of ancient Greek cities often use the local agora as a key site, for example in Kos, Delos, Athens, Messene, Corinth, Stageira, Priene, Miletus, Ephesus, and others.

One of the colonnades bordering the agora.

Thus, it is not surprising to find a large agora at the very centre of ancient Thasos, just inland from the military port. Its present layout as a large trapezoidal square (about 100 by 80m or 330 by 260ft), surrounded by colonnades, goes back to the fourth century BC. These colonnades, standing in front of elongated halls (stoas), are a standard feature of Greek public architecture, used to define, structrure and monumentalise the limits of squares and streets: to the ancient visitor, the agora was surrounded by a backdrop of over 120 columns on all four sides. Although only the foundations survive, there is much to see here, most importantly the bases for innumerable statues, many of them inscribed.

In the northeast corner is a particularly important monument, dedicated to Glaukos, a general active during the era of the foundation of Thasos, as indicated by a very early inscription (from the late 600s BC, long before the other structures now visible). It's a perfect example of a city commemorating its own history. There are also a number of shrines contained in the agora, including one to Zeus agoraios (Zeus as protector of the agora) and the aforementioned one to the athlete/hero Theogenes.

The inscription from the monument to Glaukos, a general from the earliest phase of the city's history, in the agora. Now in the Archaeological Museum of Thasos, it probably dates to the late seventh century BC, a few generations after the lifetime of Glaukos himself. It reads I am the memorial of Glaukos son of Leptines: the sons of Brentes set me up.

A foundation in the northwestern corner is interpreted as the bouleuterion, the council chamber, exemplifying the agora as the location of the political institutions entrusted with the running of the city-state in the same area. Just to the southeast of the square is a well-preserved marble-paved street lined by a long row of rooms that were probably shops - so the commercial character of the area is also visible.

Dionysos caressing a lion on a bronze vessel from a grave in the Thasos necropolis (late 5th century BC). Thasos Archaeological Museum.

Cemeteries

Like all ancient Greek cities, Thasos was surrounded by extensive necropoleis, cemeteries, outside its walls. Walking around Limenas, here and there, large numbers of sarcophagi can be seen sitting in fields and gardens, or lined up in the scattered excavations. Much richer evidence for the graves and their contents can, however, be found somewhere else: in the museum!

Additional evidence: the Archaeological Museum of Thasos

All the features listed above would already make Thasos/Limenas a uniquely informative and enjoyable experience, throwing so much light on the functions of an ancient city, approachable simply in form of a casual stroll through a quiet coastal town.

But there is more. Thasos is one of the still relatively few archaeological sites in Greece to feature its very own museum, located just next to the agora and permitting us to admire the finds from the excavations in geographic proximity to the site and in context with one another. It is one of the largest such on-site museums in the country and its collections contain a large quantity of material of great beauty and interest. Some of the artefacts confirm the features and characteristics of the city shown above, while many others throw light on countless further aspects of ancient Thasos.

One of the finest pieces in the museum is the Thasos kouros, a statue of a nude young male. Dating to about 600 BC, it is one of the earliest and one of the tallest (3.5m/11.5ft) examples of this kind of Archaic sculpture. Its most unusual feature is the sacrificial ram held in the figure's arms.

Sculpture (obviously made of Thasos marble) found at the various sanctuaries and especially in and around the agora, is well-represented in the museum, helping us to understand the development of a major art in the Greek World and how this small island actively participated in it, from its very beginnings until the Roman era, when Thasian marble became especially sought-after.

Beyond that, the exhibits permit us to trace the historic trajectory of Thasos from distant prehistory to the Roman and Byzantine eras. They also include many inscriptions, illustrating countless aspects of ancient life in Thasos, especially the political workings of the city-state and the cult practices at the many shrines.

Another fascinating element here are the finds from the graves we saw outside the walls, presenting insights into more personal aspects of ancient life and death: the offerings that were placed with the deceased, reflecting their status and wealth in life, but also their or their peers' view of their place in the world...

How to see Thasos/Limenas

The sites of Limenas are open to the visitor at a moderate fee. It is easy to get to Thasos from the ferryport of Keramoti, near Kavala in Eastern Macedonia, Northern Greece. Once there, a day's worth of time and a good map, even better a good guidebook, help along.

The best option, however, is to see the place with Peter Sommer Travels' expert guides, on our Exploring Macedonia tour. The itinerary includes nearly a full day on the island, with a thorough tour of the ancient city and a foray into the south of the island.

When visiting Thasos over 30 years ago, with our Greek family who lived in Kavala, my sister-in-law took a pebble and rubbed it on the relief of the horse tailed Silenus in the place that you surmised that it had been censored! Very many women were in the habit of doing this as they had a superstition that this would make them fertile. They said that was why it was being worn away. Well it worked for her and afterwards our nephew was born!!