Have you ever heard of Kapıkırı? Almost certainly not: it is a small, poor and quite ramshackle village of a few stone houses, a few kilometres off the main road that links the seaside resorts of Bodrum and Didim in Western Turkey. The tourist infrastructure of Kapıkırı is limited to a few rent rooms, a simple restaurant or two, a shop and the typical teahouse found in every Turkish village, as well as some ladies selling honey, embroideries and other things by the roadside. None of that is unusual - but for many of the guests we take there on our cruise From Halicarnassus to Ephesus, the visit to Kapıkırı is a highlight of the trip!

A special place to visit

Not too many visitors find their way there so far - of the ones that do, many are hikers or mountain climbers. No wonder: Kapıkırı is certainly memorable and attractive in terms of its location. It overlooks the shore of Lake Bafa, the largest inland body of water in this part of the country, and is overlooked in turn by the rugged Beşparmak Mountains. Indeed the landscape in which Kapıkırı stands is surreal and stupendous, consisting of huge rocks, many the size of houses, polished smooth by millennia of exposure.

So, the spot would certainly justify, say, a glass of Turkish tea to be consumed in that enchanting setting. But that's not why we go there: there's more to the place. Already on the road approaching the village, the visitor will spot well-built but long-abandoned walls, towers, and numerous rock cuttings, slowly revealing that the entire landscape is packed with the remains of what was once a great city, reaching from fortifications on the little offshore islands via massive foundations in the area of the modern village, to further structures scattered on the rocky slopes higher up, often in seemingly absurd locations.

A lost city and a lost sea

Kapıkırı sits on the centre of what used to be Herakleia, to be precise: Herakleia-by-Latmos (Herakleia pros Latmou in Greek, or Heraclea ad Latmum in Latin). That rider was used because the name Herakleia, derived from the hero and demi-god popular all over the Greek world and beyond, was quite common, so a specifier was added: Latmos (or Latmus) is the ancient name for the Beşparmak Mountains.

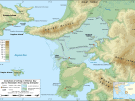

A map illustrating how the coastline of southern Ionia and northern Caria has changed since antiquity. The Latmian Gulf is centre right. (Original by Eric Gaba, Wikimedia Commons.)

Today, the relative poverty and simple houses of the modern village stand in striking contrast to the grandeur and the sheer monumentality of the ancient remains visible all around. Indeed, the location strikes the visitor as an unlikely spot for a once great and affluent city. How could an urban community have thrived here for centuries?

The reason for this strangeness is found in the profound changes the Turkish coastline has undergone since antiquity. In Greek (and Roman) days, Herakleia was a seaport! What is now Lake Bafa was a part of the Aegean Sea known as the Latmian Gulf (Latmiakos Kolpos), entered through a wide mouth separating the famous cities of Miletus and Priene. Millennia of soil deposition by the river Maeander have since closed it off, creating an enclosed lake and stifling the economic potential of its shores.

Caria and the Greeks

Herakleia is located in the region known as Caria in antiquity. There is a local Anatolian settlement not far uphill from the ancient city, most likely its direct predecessor. Like all of western Anatolia, and especially the region of Ionia just to the north, Caria received a growing cultural influence from Greece from the 9th century BC onwards, including Greek "colonies", Greek-style cities founded by emigrants from the Greek mainland or islands. Nonetheless, Herakleia as we now see it was only founded in the 4th century BC - and we don't (yet) understand the details of how that happened or who instigated it, although Mausollos, the famous ruler of Halicarnassus, a little further south, is a candidate, as are the various rulers succeeding Alexander the Great after his conquest of Anatolia a generation later.

The foundation of new cities, or the refoundation of existing ones, was a common trend in the area at the time. Usually, this entailed the decision to relocate the inhabitants of pre-existing settlements at a newly chosen or already settled site, thus urbanising an area and creating Greek-style cities as local centres of economy and power. Examples of such "new" cities are common; they include Rhodes, Kos, Knidos and Priene. The resettlement could be variously voluntary or forced, for Herakleia we simply don't know. It is certain, though, that the newly founded settlement was much larger than its predecessor. It is also clear that it was provided with a staggeringly monumental public infrastructure, especially in terms of city defences, but also of public buildings and shrines, that must have been way beyond the means of the locals.

Herakleia existed as a city for quite a long time, perhaps as long as the 10th century AD, some 13 centuries after her foundation. The city's final abandonment is probably due to the closing of the Latmian Gulf, stifling her economic potential forever.

Another model city and its monuments

Resulting from her artificial foundation, and also from the fact that she seems to have thrived most in the centuries immediately after and received little alteration during her existence, combined with the virtual absence of later occupation (except the small and recent village), Herakleia is unusually well-preserved. The site is a typical example of a planned Hellenistic town, with a rectilinear street grid defining residential areas, public squares and shrines - all the features and spaces that define Greek urbanism. In her stupendous setting, Herakleia is a true marvel, a unique and vast open-air museum.

There is so much to see. Kapıkırı village is rattling around within the confines of the much larger ancient city, occupying its very centre. The core of the modern village and the ancient city alike is a large flat area interrupting the terrain's natural slope, clearly created artificially. Today, it serves as school yard and car park, but it is actually the ancient agora, the marketplace and civic centre of ancient Herakleia. Measuring an impressive 60 by 130m (200 by 425 ft), it is supported by massive terrace walls that supported shops and contained their basements, which are still preserved extensively. You are looking at the foundations of an ancient shopping centre.

Overlooking the agora from a very striking natural outcrop is the shell of a single-roomed ancient temple, a fairly typical example of its kind. Made of local rock, it would have been clad in fine marble and embellished by a columned porch in antiquity, but even without those it still dominates its surroundings. It was most likely dedicated to Athena. Also near the agora are the remains of the bouleuterion, the ancient council chamber, now set in a private home's back garden, the scant remains of the councillors' seats frequented by chickens, donkeys and cats.

Monuments, walls and graves - and 50 babies

Walking (or scrambling further), there is more to be discovered. The area of the ancient city contains more public buildings from many periods, among them the remains of the theatre, Roman baths and a nymphaion (spring house), as well as a gymnasium (an athletic training ground surrounded by porticoes). A little south of the agora, an unusual structure with a curved back wall and a columned porch is suspected to be the sanctuary of the shepherd demi-god Endymion, who was believed to be from the area. In legend, the moon goddess Selene took a shine to him (pun intended). As she could not quite make him immortal, she extended his life indefinitely by putting him to eternal sleep in a local cave, interrupted by her nightly visits, as a result of which she bore 50 children by him. The sanctuary supposedly marks the site of the cave where he slept (or still sleeps).

The most visually arresting feature of ancient Herakleia, however, must be its incredible city walls. They are among the best-preserved of their kind (we have recently presented other spectacular 4th century BC examples here, those of Messene and Loryma, but Herakleia can easily compete), extending for more than 6 km (3.7mi), with over 40 towers. The walls still stand to a height of over 6m (20ft) in places, the towers even higher. The locations of the towers is often mind-boggling: using the natural terrain's monumental outcrops, some of them seemingly teeter on impossible brinks. The strange thing about this very monumental set of city walls (the founders of Herakleia certainly wanted the city to be safe!) is that in spite of their impressive dimensions, the even more monumental landscape makes them look like some forgotten giant's left-behind playthings...

Immediately beyond the walls, the visitor will, on a first look, spot the occasional rectangular cutting in the rock, often placed in locally prominent outcrops. Having noticed first one, then another two or three, he or she will soon realise there are dozens, hundreds, even thousands, surrounding the city walls. These are - quite simply - rock-cut graves, as usually placed outside the confined of the city. Their large number witnesses the long existence of Herakleia.

More to explore

For the more intrepid explorer and walker (the Carian Trail passes through Herakleia), there's even more to discover. A few minutes uphill from Herakleia are the scant ruins of the Carian predecessor settlement. Also, the area contains dozens of caves, some with prehistoric paintings, others with Byzantine frescoes. Truly committed hikers can also seek out the remains of multiple Byzantine monasteries high up in the Beşparmak mountains to the north. From the 7th century onwards, that area was settled by monks from Mt Sinai and, for a short time, functioned as a "Holy Mountain", not unlike Athos in Greece still does.

We show Herakleia to our visitors on From Halicarnassus to Ephesus, an epic 2-week cruise taking in some of the most famous archaeological highlights in Western Turkey, but also less well-frequented gems like this one.

Leave a Reply