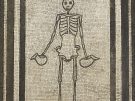

Roman mosaic showing a skeleton holding wine jugs, from Pompeii's House of the Vestals.

Well, there can’t be many exhibitions more calculated to have Peter Sommer guides and travellers alike sniffing the air and perking up like a meerkat than this one. A food- and dining-related exhibition focussing on one of the most famous ancient sites in the Roman world? That’s two of our major spheres of activity thrown together, though admittedly food on our tours tends to be a heck of a lot more edible, and dormouse-free, and the diners are a lot more lively, at least until the dessert’s all gone. With all that in mind, a visit to the exhibition at the Ashmolean was essential.

The exhibition is designed to lay out the whole food story of Pompeii and its neighbouring sites on the Bay of Naples: how it was produced, sold, cooked, eaten ... and so on. But it’s about more than that, too. It’s also about the historical origins of those dining practices and how the Roman culture of Pompeii was actually multi-stranded, and drawn from different cultures (Roman, Oscan, Etruscan, Greek) and not monolithic across the Empire. That point’s then extended towards the end of the exhibition with a parochial (in a good way) take, showing how the Roman practices we’ve been introduced to played out in Britain where they interacted with local and provincial fashions. It’s a good way of coming to see that not all ‘Romans’ were the same, and introduces a nice dynamism to the viewer’s understanding of imperial culture.

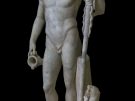

Marble statue of Bacchus with a panther; AD 50–150, from the ruins of a temple in Piacenza Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

The Ashmolean’s exhibition space is fairly sizeable, and well-filled. Remember how it’s broken down: firstly the cultural origins to Pompeii’s imperial dining habits: Greek, Etruscan and Italic. Then a look at the local food and drink production and how it gets to the shop front. We’re then taken through the Roman house and its different food environments – garden, atrium, triclinium, kitchen and toilets. We then come to Britain and look at its similarities and differences, before a final reminder of the eruption.

All this means that not all the exhibits on show are from Pompeii or the other sites that fell victim to Vesuvius – Herculaneum, Oplontis and so on. The first main room is composed of material from the wider region of southern Italy dating back centuries before the eruption; the last is largely material from Roman Britain. Now, it’s possible to grumble about this and say you’re not getting an entirely Pompeian exhibition. I think this would be misguided and unfair: there’s really a lot of Pompeian material here. Some iconic - and large - pieces have come thanks to the efforts of the curator, Paul Roberts, whose contacts since overseeing the British Museum’s excellent exhibition on the site back in 2013 are evidently still superb. There’s more than enough really good material from the AD 69 eruption to satisfy anyone. Treat the rest as a fantastic bonus. Some of it’s from sites or cultures that we don’t get to see a lot of in Britain (the material from Paestum and northern Italy is particularly interesting), some of the British material hasn’t been much seen outside of London, and some of it is effectively appearing for the first time. There’s certainly enough non-Pompeian material here to give even the most blasé viewer who’s tired of the highlights enough cause to come. Much of this variety is down to the generosity of lenders: Pompeii’s Archaeological Park itself of course, but also the National Museum in Naples, the Paestum Archaeological Park and in Britain the British Museum, the private Wyvern Collection and Chester’s Grosvenor Museum among others. There’s definitely stuff here you won’t have seen.

Fresco panel showing a dinner party with painted messages: FACITE VOBIS SUAVITER EGO CANTO and EST ITA VALEAS (make yourselves comfortable; I am singing; go for it!); AD 40–79, Pompeii, House of the Triclinium. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

With eruption Pompeii snapshotted, we then wind back to those antecedents, the cultural strands that made up the version of Roman culture that applied there. There are some excellent Etruscan cinerary chests from the British Museum, a characteristic find from the culture, with scenes usually from myth below the reclining, dining figure of the deceased above, all picked out with plenty of colour. It’s nice to see them afresh in a different setting.

Painted Etruscan funerary urn and lid with heroic battle scene and Etruscan inscription: Thana Ancarui Helesa (Thana Ancarui, wife of Hele). The lid (which does not belong to the urn) is in the form of a reclining young man; Chiusi, Tuscany 150–100 BC British Museum, London.

Two in particular grabbed me: one with a vivid battle scene presided over by a lid featuring a woman, Thana Ancarui Helesa (it turns out the two don’t belong together) and one dominated by the splendidly hangdog expression of Aule Latini Pultus. Their dining paraphernalia’s there too: candelabrum, incense burner and the ladles and strainers to remove residues, spice, onions and even the cheese that went into flavouring the wine. You see how it all works? I don’t want to leave this room without drawing attention to two other sections. One is the magnificent pair of fourth-century BC Lucanian tombstones from Paestum – a rare sight in Britain! – one with a striking gorgon face gazing directly at us. These were a highlight for me. Just next to them was another, a terracotta plate with model food on it, again from the mid fourth century. One item on the plate particularly screams out to a British viewer (I wish I could say I was the first to note it, but it’s far too obvious to claim unique insight), and that’s the one that looks for all the world like a custard cream biscuit. Honestly, these bits alone were worth the journey to the Ashmolean for me.

Terracotta votive food: pomegranates (open and closed), grapes, figs, almonds, cheeses, focaccia, honeycomb, mold, long bread, 360 BC, Tomb 11, Contrada Vecchia. Agropoli Parco Archeologico Di Paestum.

A custard cream biscuit, for essential comparison purposes with the item at the nearest part of the plate above. From Wikimedia Commons.

It’s tempting to play along with the food metaphors and announce the end of the entrée, and what a way the exhibition chooses to wheel in the next course! The linking vestibule greets you with the iconic wall painting of lushly tree-clad – and intact – Vesuvius, Bacchus standing by festooned with grapes. It’s good to be able to get close to the painting, and see the quality of the brushwork on the figure, and the glistening luminous quality of the swelling grapes festooning him. It certainly whets the appetite for the following sections (look, I can’t stop. You try writing this without thinking about eating). We come first to the story of food production in the bay of Naples, and there’s some really interesting stuff here. There’s meat, in the form of a pig plaster-cast in the well-known manner from the void its body left at Boscoreale’s Villa Regina (a cast in this case, but indistinguishable from the real thing), and fish sauce in a clay bottle with a painted label telling us it’s the finest garum of Aulus Umbricius Scaurus. Gathered together, the objects really give an impression of a rich and fecund landscape. There’s the still-stoppered glass bottle of olive oil, the contents visible within and still giving off the odour; an amphora declaring it contains a sample of a 100 ton shipment of African corn (grain) and a really splendid relief, full of vigour, of a giant wine-filled ox-skin, a culleus, straining and swelling while being drawn on a cart. One of the nicer features of the exhibition is the attention to fairly new excavations, and here we’re introduced to the site at Scafati, which produced a ton of pomegranates, an amphora of pitch for sealing and the jar used to boil it all up, cultivation tools and images of the vine cultivation ridges found by the archaeologists. You can almost feel the thick summer air and touch the leaves of this just one of the villas bursting forth with produce for the bay cities.

Rhyton (drinking or pouring vessel) in the form of a cockerel, AD 1–79; Pompeii, House of the Venus in a bikini. Parco Archeologico di Pompeii.

From soil to shops next. We’re treated to the famous tavern sign of the Phoenix of Euxinus; ‘the Phoenix is happy’ runs the strapline, ‘may you be too’. Around this there are other, similarly famous, exhibits – a carbonised loaf from Herculaneum (the city famously destroyed by the same eruption that ended and conserved Pompeii), juxtaposed with the famous wall painting of the distribution of identical loaves (not from a shop, but as an inducement at an election to the outstretched arms of floating voters). A kitsch deep terracotta Kellogg’s-style cockerel jug stands ready to pour from its beak, while a terracotta stove with a triconch-end looks almost like an Egyptian soul house. It’s fascinating stuff that might be lost to the eye in a different format. Particularly interesting are some vessels in a partial state of preservation, here because, for the first time, an institution outside Pompeii has been permitted to conserve them. We see a kettle still with limescale, and other bronze vessels still crusted with lapilli from the eruption and turned an azure blue by the high temperatures, a distinctively Pompeian feature. Every section has something special like this.

Fresco showing the distribution of bread, AD 40–79; Pompeii, House of the Baker. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

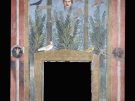

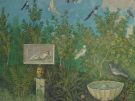

Fresco wall from the House of the Golden Bracelet, Pompeii; AD 1–50 Parco Archeologico di Pompeii.

The main course, if you like, is the next section, in the largest and most open of all the areas in the extensive exhibition space. Here, we encounter the high-status house and its various food arenas. An excellent job is done of establishing the environment with wall paintings, mosaics, shrines and so on, providing a great backdrop for the dining objects themselves. The combination of food, cutlery, images of how they were used and the surroundings again works extremely well, making this a most attractive and convincing part of the exhibition. Particularly charming in the garden is a bronze piglet – resembling nothing so much as the one which enamours Homer in The Simpson’s Movie – with an inscribed dedication to Heracles, and the roof-tile repurposed as a portable altar, together with the remains of sacrificial meals: burnt piglets and lamb bones, carbonised figs and grapes, even eggshells. The setting is vividly sketched by a tortoise-shaped fountain spout, pierced plant-pots, water pipes, and the great garden fresco from the House of the Golden Bracelet.

Mosaic panel (emblema) showing fish and sea creatures; first century BC, Pompeii, House of the Geometric Mosaics, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

The dining room is evoked in the same way. Mosaics and wall paintings help again, including the unique one of an all-female meal and the Europa fresco (another icon – well done Ashmolean). You’ll probably want to spend a little time with the extraordinary sea-life mosaic with its carefully recreated population of delicious aquatic life, its eye for detail allowing you to identify each future morsel down to sub-species - this is a mosaic that will provide material for discussion for generations to come, as it has domne since its discovery. Theere’s a really grand selection of dinner vessels in the centre of the display, ranging from the everyday to stupendously ornate silver masterworks drawn from the Arcisate Treasure, not from Pompeii, but rather Lombardy in the late Republic, well over a century before the eruption. You’ll not complain when you see it – it’s absolutely amazing.

Fresco wall panel showing Isis Fortuna protecting a man flanked by the agathodaemones (protective serpents), with painted message: CACATOR CAVE MALU[m] (‘crapper beware the evil [eye]’); AD 40–79, Pompeii, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

Finally, for the main Pompeii section, we check in with the kitchen staff. There’s a nice range of preserved food from the site – grains, sea urchins, beans, oysters and walnuts, a well-observed fresco of a rabbit munching some figs, and remains of garum. Right next to it, though, is a reminder for all the impressive facilities we’ve just seen, the Romans aren’t all sleek modernity in where they typically locate the toilet - next to the kitchen. It brings us another item from your Pompeii (slop-)bucket-list: the wall painting from a corridor outside the toilet of a caupona, showing Isis Fortuna with her rudder with the vulnerable and naked figure of a squatting toilet user. Written beside is cacator cave malum, gently translated for the benefit of the exhibition as ‘crapper, beware the evil eye’. We round off our visit ‘below stairs’ with a look at food preparation and storage. There’s lots to interest amid the griddles, cake-baking pans and colanders, but you’re likely to particularly enjoy a few things in particular. There’s the wall painting of the cockerel, the subject and palette making it look like a loan from the seventeenth century Netherlands rather than Pompeii, and the pierced ceramic jar for edible snails. I was particularly glad to see – another a first encounter at the British Museum exhibition – a glirarium, the specialised pot to hold dormice and allow them to scamper around and become more delectable.

Fresco showing a cockerel pecking at figs, pears and pomegranates, AD 45–79; Pompeii, House of the Chaste Lovers, Parco Archeologico di Pompeii.

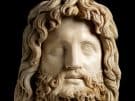

Marble head of the god Serapis wearing a modius (grain measure) AD 180–200; London, Walbrook Mithraeum © Museum of London

After Pompeii, Britain. We’re shown how Britons were already importing Mediterranean-style food and drinking forms before the Roman conquest, and then we see the increase of the overlap between the traditions through Roman rule – a parallel to the strands we saw making up Pompeian dining. So, to things familiar from previous rooms - imported amphorae, chicken bones from a sacrificial feast (to Mithras in London in this case), panpipes from Shakenoak villa - are added distinctly British beer and beef. Some of these British objects rival Pompeian material for the quality of the preservation: celery seeds, plum stones, a wooden barrel head, a wooden valve from a fishpond, peppercorns from India, even cockroach eggs from a late first century bakery in Roman London (the first attested cockroaches in Britain, no less). The British material also manages a few icons and pieces you’ll maybe know from news stories – a knife-handle with mating dogs from Silchester, writing tablets from the Bloomberg site in London with a food contract of AD 62. There’s also the stupendous very recently discovered inscribed stylus from London which got a lot of coverage - the first time I’ve been able to see it (sadly admittedly the lighting doesn’t pick out much of the detail). We finish the British section by some excellent tombstones from Chester which make me definitely want to re-visit the Grosvenor Museum, showing the deceased reclining at dinner – and this is where we came in.

So how do we leave? Appropriately, we’re given a last taste of material from around Pompeii. At the centre of them, as in an unspoken way of the whole exhibition, is not an item of food or an implement, but a person. This is the one body cast at the exhibition, the resin lady from Villa B at Oplontis. She now lies outstretched but, if the images on those tombstones from Chester are to be believed, perhaps she dines in eternity. It’s a reminder that the wealth of knowledge the sites of Pompeii have given us, so richly presented in this excellent exhibition, was dearly bought by the people whose last meals were taken in late AD 79.

The body of a woman in her early thirties, preserved in transparent epoxy resin; AD 79, Villa B, Oplontis.

Leave a Reply