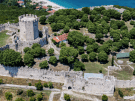

It would almost take an act of will to miss Platamon Castle as you drive south out of Macedonia towards Thessaly, so prominent is it on its rocky eminence, around which lesser roads swirl bewilderingly. And such an act of will would really be folly, because apart from the obvious military importance of its perch high above the sea, the remains of the castle, forming a stony diadem crowning the rounded summit of the hill, give it a singularly attractive quality. It very much gives the impression of being a building that wants you to know it’s a castle. It could quite easily stand for one in some visual dictionary, with its pale grey enceinte wall standing out against a lush dark green shawl of trees and its burly octagonal great tower, the donjon, thrusting its way skyward against the intense blue of the Macedonian sky. There we are: a castle with an inner bailey and a great outer one, as clear as day in an aerial photograph. A textbook view.

The fourteenth century donjon

But despite the apparently open-and-shut case, there’s actually quite a bit more complexity to Platamon than this. Though the interior seems relatively sparsely furnished with buildings, that hasn’t always been the case, and indeed the term ‘castle’ only becomes applicable relatively late in its history. Here and there, there are indicators of what’s gone before, if you know where to look and how to read what you see.

While it may not always have been a castle, that ‘fortification’ has been a major part of its reason for existence is clear. The rock it caps stands high above the terrain around, scattered though it is with hills, bumps and knolls everywhere which rise up through the foothills to the ever-present dominating mass of Mount Olympos. Platamon’s hill pinches the terrain below to manageable proportions for those wishing to control the land routes passing it, and overlooks likely spots for a harbour on the run to historically important places like Thessaloniki. And it does so as the first place in Macedonia proper: stand on the hill and look south, and you see the terrain remains constricted. Effectively just a little beyond and ‘round the corner,’ so to speak, you have the Pass of Tempe, the narrow ‘doorway’ between Macedonia and Thessaly – or Greece and Macedonia, depending on your viewpoint. Platamon was the lock to this doorway.

A seventeenth-century Turkish cannon on a somewhat makeshift carriage

There were ways around it, of course, if you detoured inland, losing time and supplies, but if it could be held in strength, Tempe offered a real headache to passage, and this was recognised early on when the Greeks considered making their stand here rather than at Thermopylae. The advantageous position had already seen a town, Heraclea or Heraklion, grow up on the very hill Platamon castle would later occupy. The Macedonian kings recognised the value of the place, and it served them well: it stood squarely in the way of the great Spartan general Brasidas and later invaders until it finally fell to a Roman force just before the kingdom itself in the second century BC. The account of that assault is, it has to be said, a little unclear, but we need to be grateful for it, since for all its strategic value, Heraclea-Platamon barely troubles the ancient historians with its existence – at least as they survive for us. It was clearly more involved in events because there are signs of it having been attacked and at least damaged more than once. We can’t say much more than that, because the ancient remains lie under all those of later periods, but if you go to the right spot on the castle’s outer walls, you’ll find tell-tale large honey-coloured blocks that formed the town walls of Heraclea, and archaeologists have found traces of houses and workshops inside.

Church with traces of wall paintings

The Roman period is largely a blank, Heraclea lying far behind the frontiers, but by the time of the later Roman empire that had changed, and once again the hill was a fortified settlement, by now having lost its ancient name and taken on its medieval one of Platamon. We hear a bit – but not much of it – in the Byzantine period, when it seems to have been flourishing, if the account of the Arab geographer al-Idrisi, writing in the service of the Norman kings of Sicily (for whom, see Exploring Sicily!) is to be believed. Archaeology adds to the picture, especially with a series of churches, one of them adorned with intricate marble sculpture.

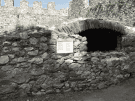

One of several cisterns on the acropolis. A secure water supply for the garrison was clearly a concern

The main gateway and its covering tower

But it’s in the later medieval period that Platamon transforms. Up until this point it largely remained what it had been: a strongly fortified hilltop town.

With the thrust to the Byzantine jugular of the Fourth Crusade, everything changed. The ordered edifice of Byzantine Macedonia collapsed and for the next two centuries, the region became a whirling and confusing arena of contending powers. Platamon first came into the hands of the abortive Frankish Kingdom of Thessaloniki, but not for long. Regained by the renascent Byzantines, it was at times in the hands of Venice, Epirus and the Turks, and threatened by others besides. The fourteenth century in the Balkans, in particular, was not a period which one would wish to time-machine your way to. And it’s then, in the last phase of Byzantine control, that we see the true castle emerge, with its closed off acropolis fortifications and that hefty, imposing tower, some of this work handily dated to the year by the sort of inscription you’d wish appeared more frequently. What you might call the outer bailey, if this were that straightforward castle, was still occupied by a Greek town, and continued to be with the inevitable Turkish conquest, when the castle remained a stronghold. Not much is now visible in the interior apart from the churches, not least because, as Greeks became more suspect to the Ottomans, this community was by the nineteenth century expelled. The town did not die, though: it became a Turkish and Albanian one, the garrison keeping an eye on Greek insurgents or on bandits as the occasion demanded. Turkish style houses sprang up and mosques replaced churches or turned them into storehouses.

Church A, in the lower part of the castle, has a complex history and the remnants of wall paintings from its last phase, in the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries

There are traces of these last phases: several ruined churches, much altered over time, can be seen, some still with vestiges of wall paintings clinging to the walls, have been found. There seem almost too many churches when you look at the space between the trees in the stony interior. Where did the people fit? Well, we can find some of them – either in the teeming Greek cemeteries or in the excavated platforms of Turkish houses, blacksmiths, workshops and bakeries. But what’s been excavated of those so far doesn’t bespeak a dense population. That’s misleading though: there’s clearly more to come, since François Pouqueville, a French visitor of the early nineteenth century, tells us there were fully 150 Turkish houses within the walls. This really transforms the visitor’s impression of the place, from being a largely open space with rocky outcrops and the occasional tree to one thick with buildings; it’s a real surprise, and yet it’s largely confirmed by another French visitor a decade or so later, Felix de Beaujour. All these houses, he says, get in the way of the garrison’s ability to move cannon, and to defend the place properly. So we have to think of a thickly occupied summit, crammed with houses and narrow pathways snaking their way round the castle, old men chattering under eaves and busy work around the hot fires of the blacksmith’s and the bakers within the now-crumbling walls of the fortifications, as much a settlement as it’d been in the far-off days when it was called Heraclea.

The ‘acropolis’ in the southwest of the castle

All this came to an end later in the century as the castle became less and less defensible against modern attack. It did have a last hurrah as a frontier post with the emergence of the Greek state, and was battered by the Greek fleet in 1897, but with the Balkan Wars of the early 20th century, it passed into Greek hands. And then its life as a fortress ended; and so did its life as a town, as the Turkish-Albanian townsfolk found themselves ousted in turn, victims of the Exchange of Populations. But that’s not quite the end. Platamon had one last military epilogue, where it returned to its roots as the choke point doorway between Macedonia and the south of Greece, and that happened as late as 1941, when the position was defended by people whose existence their predecessors could not have comprehended. In April 1941, the Germans irrupted into Greece from the north and armoured columns unexpectedly pushed south from Thessaloniki towards the road and rail line that ran under the castle rock. Shortly before, New Zealand troops – not many, not enough – had been placed here to seal the right flank of the Commonwealth forces operating further west.

If the Germans managed to burst through here, they could turn the flanks of that force and potentially inflict a disastrous encirclement. Nobody much expected this, though: given the toughness of the approach, there was no reason to expect a strong attack, certainly not one with tanks.

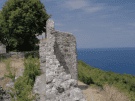

The curtain wall overlooking the north Aegean

And yet…

The story of the following days can better be told in person overlooking the site, but suffice to say those tanks did come, and for a last occasion, Platamon hill was held amid the boom of modern artillery and rattle of machine guns, for a short time at least. Just long enough. Nor did the old castle come out unmarked: German bombardment took down some of the venerable old walls, so you’ll see them now in places looking more complete from subsequent rebuilding than their dilapidated pre-war appearance!

That rebuilding is part of the programme of excavation and restoration that allows the place to be properly appreciated and admired now. The great tower remains wonderfully imposing, stark against the azure sky, the hills around are beautifully verdant skirts for glowering, snow-clad Olympos, and the view south is mightily impressive. The casual visitor can still come and go thinking they’ve seen a grand but typical castle, but since you’re here with us, you know that’s deceptive and there’s been more to it than that. This hill has seen soldiers of the rising Roman republic pour over its city walls, Orthodox priests leading services with incense and chants, haughty Frankish knightly lords, lowly Byzantine political prisoners, curious western antiquarians, bustling Albanian townspeople and doughty Kiwi gunners taking on grey Panzers. Nowhere in Greece is really an open-and-shut story, but Platamon is a masterclass in showing just how much can be teased out of something that looks like a simple tale.

To visit Platamon Castle with one of our expert tour leaders, why not join one of our Exploring Macedonia tour.

Leave a Reply