"Another thing" is a series of occasional posts, each presenting a particularly interesting, beautiful or arresting object on display at one of the museums or sites on our tours.

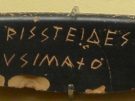

A set of ostraka bearing the name Themistokles, son of Neokles, part of a large series found in a well on the northern slope of the Acropolis. (Agora Museum, Athens)

A series of smallish, circular and concave pottery disks, all covered in a shiny black slip and all with letters incised around the edge. Not too exciting at first sight.

Au contraire, these objects are a fascinating instant of direct and tangible physical evidence for the workings of the extraordinary political experiment that was ancient Attic democracy. They are on display in the Stoa of Attalos on the Agora, the civic and commercial centre of ancient Athens.

So, what are they?

They are ostraka, inscribed potsherds used for the institution known as ostrakismos or ostracism. The ostrakismos was a unique and highly characteristic phenomenon that played an important role in the city's politics during the 5th century BC. In all likelihood, it was introduced during the reforms of Kleisthenes in 508/507 BC, when the Athenian constitution was reorganised on democratic lines after four decades of tyranny by Peisistratos and his descendants. Its aim was simply to prevent excessive power from accruing in the hands of a single man and thus to make further tyrannies impossible. For that purpose, the politician seen as the most dangerous and ambitious at the time was forced into a ten-year exile and thereby removed from the city's political life.

An ostrakon inscribed with the name of Perikles (son of Xanthippos), the leading politician of mid-5th century BC Athens, responsible for the Classical redesign of the Acropolis.

The procedure was as follows: Every winter, the full assembly of Athenian citizens (i.e. free adult males) was asked whether it wanted to hold an ostrakismos. If a majority - not counting less than 6,000 - agreed, the event was held two months later. For this purpose, a large area within the Agora was corralled off. Every citizen could enter. On doing so, he handed a potsherd (ostrakon) to an official, inscribed with the name of the individual he wished to see ostracised, further identified by his father's name and the deme (district) he came from. To prevent multiple votes, the citizens had to wait within until the vote was complete. The sherds were then counted and the person most frequently chosen, again subject to a minimum of 6,000 votes, was ostracised.

The ostracised citizen was given ten days to settle his affairs and leave Athens. His citizenship was not affected, nor was his property touched, and he retained access to its proceeds. He was not to return to the city for ten years - on penalty of death - unless a public vote recalled him at an earlier date. Ostracism was not considered per se dishonourable; status and rights were fully reinstated on return.

View of the Agora, the political heart of Classical Athens, overlooked by the Acropolis. Visible on the back left is the Stoa of Attalos, now the Agora Museum, where the ostraka discussed here are displayed.

It appears to be the case that the assembly opted to hold an ostrakismos only fairly rarely. We know of no more than 13 individuals who were ostracised in the course of a century, mainly in the 480s and 470s BC, when Attic democracy was still quite volatile, in the 450s and 440s, as Athens was turning into an aggressive imperial power, and briefly between 417 and 415, during the Peloponnesian War. The procedure had been abandoned by the end of the 5th century BC.

The ostrakismos, along with much of the Classical Athenian constitution, has been well understood for a long time, namely on the basis of historical reports, i.e. in the form of abstract book knowledge. One of the most fascinating aspects of Athenian archaeology, however, is that it has revealed actual hands-on evidence for the institutions and practices of the ancient city's political system. In the Agora, visitors can view the remains of various public buildings, including the bouleuterion (or council chamber) and the prytaneion, where the officials of the current executive resided. The meeting place of the full citizens' assembly, the Pnyx, is preserved on a nearby hill. Inscriptions recording government decrees, treaties and other acts have been found throughout the ancient city.

Archaeologists have also discovered ample evidence for the ostrakismos. Over 11,000 ostraka are known by now, the vast majority of them found in refuse dumps in the Agora and Kerameikos excavations. Most of them are quite roughly incised into fragments of coarse pottery, but in some cases they were more carefully produced.

Ostrakon made from the base of a fine kylix (a wine-drinking cup), with the name Themistokles, son of Neokles.

Our main picture shows a sample from 190 ostraka found in a well on the Northern Slope of the Acropolis, all of them inscribed on the bases of fine black-slipped drinking cups and all bearing the name of Themistokles, son of Neokles. Themistokles was one of the key leaders of Athens in the 480s and 470s BC; he is credited especially with his leadership during the Second Persian War, when he convinced his fellow citizens to temporarily evacuate the city, leading to its occupation and destruction by the Persians, but also to the eventual Athenian victories by sea at Salamis and on land at Plataia. There appear to have been several attempts to ostracise this undoubtedly ambitious man, eventually succeeding in or before 471 BC.

What is interesting about the set of sherds, probably from one of the earlier and unsuccessful campaigns, is that they are remarkably uniform and include several sets of multiple sherds inscribed by the same hand - indicating either systematic voter fraud or (more likely) an entrepreneurial spirit, as someone produced clearly legible ready-made sherds and made them available to aspiring voters for a small sum.

Further ostraka bear the names of various other well-known politicians from Classical Athens, including the most famous of them all, Perikles, who was never successfully ostracised. Especially charming is the presence of ostraka incised with the name of Aristeides "the Just", a key opponent of Themistokles, ostracised in 482 BC, but recalled soon after. In his life of Aristeides, Plutarch recounts a characteristic anecdote of Aristeides' ostracism:

As the voters were inscribing their ostraka, it is said that an unlettered and utterly boorish fellow handed his ostrakon to Aristeides, whom he took to be one of the ordinary crowd, and asked him to write Aristeides on it. He, astonished, asked the man what possible wrong Aristeides had done him. ‘None whatever,’ was the answer, ‘I don't even know the fellow, but I am tired of hearing him everywhere called 'The Just.'’ On hearing this, Aristeides made no answer, but wrote his name on the ostrakon and handed it back. (Arist. 7.5-6)

You can see some of the original ostraka, along with many other fascinating things and places, on our Exploring Athens tour.

Leave a Reply