Gold plaque in the shape of a coiled panther; Gold; 4th – 3rd century BC; Siberian Collection of Peter the Great. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin

Scythians: Warriors of Ancient Siberia follows on in a way from the British Museum’s recent Celts exhibition in being an overarching introduction to a whole people. This isn’t unlike the BM’s run of exhibitions centred around famous monarchs (Hadrian etc), and it would be good to see it continue, especially where, as here, it fills a gap in British museum collections. (I have a few suggestions if they’re wondering who to do next.) Up until now, if you wanted to see Scythian material in the UK, bar a few pieces in the British Museum itself, you had to go to the Ashmolean in Oxford. That’s no chore – seeing the Scythian material is what took me to the Ashmolean for the first time years ago – but it’s nice to see so much of what, until now, I had only seen in books. This is one of those exhibitions that allows you to ‘tick off’ a swathe of the major objects you’ve always wanted to see.

Horse and man Drawing. Reconstruction of Scythian horseman based on the excavated finds from Olon-Kurin-Gol 10, Altai mountains, Mongolia. By D. V. Pozdnjakov, Institute for Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

‘Scythians’ is a name given to a broad grouping of Iranic-speaking steppe nomads (though some under the umbrella-name were sedentary) living in wide steppe region from the Ukraine through the north Caucasus and east beyond the Caspian to the borderlands of what is now Mongolia, appearing from the time of the late Assyrian empire and remaining important until Hellenistic times. Broadly and simplistically speaking, they fill a similar historical niche to the later Huns or Mongols. They emerge frequently, and often threateningly, into history in the later Assyrian chronicles and oracle requests and particularly in the Greek historians. Herodotus has a great deal to say about them, Arrian’s Alexander finds them a challenging opponent, and they appear on Achaemenid Persian royal monuments as enemies and subjects. So they’re a pretty important group, both in their own right, and for the way the settled powers used them as a mirror, or Other, to themselves.

The exhibition is built around a core of objects from the Hermitage in St Petersburg, who’ve clearly been very generous. As much of this collection originates in the Siberia of Peter the Great, it does mean the focus is a little bit more on the eastern part of the Scythian world than I initially expected, and less on the Greek fringes and Caucasus, but given the quality of the material, and its relative unfamiliarity, that’s no bad thing. And there is material from the Ashmolean collection and Russian sites like the Kul’ Oba tumulus, so the west isn’t neglected.

A gold belt plaque of a Scythian funerary scene; Gold; 4th–3rd century BC; Siberian Collection of Peter the Great. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V Terebenin

It’s well-arranged, beginning with a bang – a mass of golden treasures – plaques and torcs – that are the most famous Scythian visual legacy. It was these that I was expecting to be the bulk of the exhibition – I was wrong about that, I’m glad to say: there was enough gold to satisfy and amaze, but far more than that, too. The goldwork is every bit as fine as you’d imagine, and thoughtfully displayed in the first room with the skilful original eighteenth century paintings of them as newly-found. All these wonders lie under the gaze of a suitably colossal Kneller portrait of Peter the Great himself from the Royal Collection, and surrounded by designs and images of Peter’s Kunstkammer museum. Kudos to the curators for that.

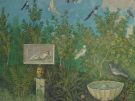

The gold plaques frequently and brilliantly depict in the ‘animal-style’ feline predators savaging horses, yak or deer: vigorous, powerful and distinctive images, whose juxtaposition introduces nicely the breadth of the Scythian world and its interactions with Greek, Near Eastern and Chinese imagery, as well as the native vitality and power of Scythian art. Other images hint at probably-irrecoverable Scythian myths. One apparent exception to this oblivion is the superb Kul’ Oba vase which, with the help of ancient Greek historians, is plausibly reconstructed as depicting a Scythian foundation myth involving Hercules and the stringing of a bow. It’s fantastic. The gold alone would be worth making the trip to see, and constitutes a decent proportion of what I’ve drooled over in books over the years. Some pieces turn out to be far smaller and more intricate than I’d imagined from photographs. One, though, turns out to be much larger than I’d envisaged: the C7th BC deer from Kostromskaya (Kuban) is huge for a gold plaque, fully 31.7cm across and very impressive.

Southern Siberian landscape with burial mounds. © V. Terebenin.

Surrounding the rest of the exhibition is a backdrop of images of the terrain the Scythians had to exist within – thick forests, arid rocky valleys – which helps fix the challenges they faced in our minds. It’s accompanied by some soundscapes – winds over the steppe, galloping horses – of a sort the BM has experimented with in recent exhibitions. I know it sounds possibly awful as an idea, but it’s done with some restraint here, isn’t too intrusive, and is often evocative. There’s also a large and rather hypnotic projection of a steppe-scene with a horse archer practising which will keep the kids busy, and yourself if you allow yourself to stare too long. The emphasis on the environment is a good one: there’s a strong feeling of scale and space, of varied landscapes at turns hostile or resource-rich. Chiefly, though, we get a sense of cold, hard places to live that would be at home in a wildlife documentary. Steppe Planet.

Part of human skin with a tattoo. From the left side of the breast and back of a man; Pazyryk 2, Late 4th-early 3rd century BC.

© The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V. Terebenin.

That harsh, cold world produces an immense advantage for us, archaeologically. The Siberian excavations, in particular, have produced an enormous wealth of organic material that allows us to see far beyond, and below, that amazing gold. For all its brilliant lustre, the treasure almost plays second fiddle to the everyday and the organic here. The superb preservation allows us to see the Scythians much more clearly and broadly: clearly, because we can see their very clothes, skin and adornments; broadly because we are not restricted – as we all-too-often are – to the more-easily-preserved possessions of the wealthy. There’s much to awe, so I’ll pick out a few personal highlights. In terms of the people themselves, we have the unsettling and extraordinary find of the skin of Scythians early in the display. The intricately-tattooed, leathery, arm and torso of a chieftain buried in the Pazyryk-2 mound in the fourth/third centuries BC, and his battered and scalped head make for an absorbing and uncomfortable encounter. Considerably less gruesome, but again showing the ordinary-as-extraordinary are the blackened nail clippings, around 2,400 years old, likewise from Pazyryk-2, complete with original leather bag. The remnants of fabrics and footwear in a slew of colours, with beautifully-carved and gilded headdresses allows for some excellent reconstructions.

Further on, and initially incomprehensible, but a delightful surprise when you read the label, are the chalk-ball like remains of cheese. Strange, unexpected and sweet is the felt swan which for all the world looks like something from a child’s room a couple of generations back, and like nothing I’d have imagined from that period (C3rd BC) and region. Nearby, and brilliantly illustrating Herodotus’ account of stoned Scythians, is a felt-covered hexapod tentlet for smoking hemp, complete with preserved hemp seeds. The Scythians’ brilliance as mounted warriors is amply covered – elaborately-decorated horse-harness and saddles, wicker shields, scale armour and an array of arrows, some with painted shafts surviving, one with a finely-inlaid head. There’s far too much to comment on, I’ll have to leave out great things like horse-tails and jewellery, but the richness and sweep of material should be coming across. Not everything is small or portable either: there are some magnificent early standing stone markers, and the huge complete wooden chambers and sarcophagi from the core of elite burials. Take plenty of time, you’ll need it to maximise the experience.

Horse headdress made of felt, leather and wood; Pazyryk 2; Late 4th-early

3rd century BC. © The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2017. Photo: V. Terebenin.

The exhibition ends with some Altai cultures after the Scythians. There is a connection, but my feeling was that it was as much because this material was available as because of the narrative that could be presented. That might sound like a complaint, but again the quality and interest means they’re more than welcome: the painted funeral masks, and skin-clad skulls beneath from Oglakhty are wonderful and not the sort of thing you often see here. This is really a superb exhibition, and a brilliant collaborative effort.

The catalogue is good, but pricey (though occasionally the translation from Russian is a bit stilted, and it’s a shame such an archaic translation of Herodotus was used).

The exhibition runs until January 14th. Standard entry for over-16s is £16.50 (members free).

(All images used in this post are from the British Museum's press release on the exhibit. Copyright information is in the image captions.)

De toute beauté.Ça vaut la peine de faire toutes les démarches nécessaires.