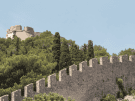

If you set sail from Split and head south through the Split Gates—formed by the tips of the islands of Brač and Šolta—the next island you’ll encounter is Hvar, the longest island in Croatia and the fourth largest overall. Soon, the port of the town that shares its name with the island comes into view. As we enter Hvar Town, on our cultural gulet cruises, we are immediately struck by the impressive fortress dominating the hilltop, rising 100 meters above sea level. This fort has long protected the harbour and the walled city below, casting a mighty shadow over the bustling waterfront. Though it shares its name with the island, Hvar Town is the largest—but not the oldest—settlement here. What’s truly fascinating is not only the visible landmarks but also the rich layers of history buried beneath the town’s streets and squares. Let’s explore what lies beneath our feet as we stroll through the narrow, winding alleys of Hvar Town.

Aeriel view of the Fortica (fortress) and harbour of Hvar

We begin our tour at the fortress, known as Fortica, a Croatised version of the Italian "Fortezza." Even beneath this fort, older fortifications once stood. The oldest traces date back to the Iron Age (about 1000 BC) when a hillfort served a similar protective role for Hvar’s early inhabitants. In the 13th century, the first medieval fort was constructed with four rectangular towers, remnants of which are now embedded in the foundations of the current structure. The Fortica as we see it today is primarily the result of a Renaissance reconstruction following two tragic events.

In 1571, Ottoman raiders attacked, pillaging and burning much of Hvar town, but the fort held firm, providing refuge to the town’s residents. Eight years later, a lightning strike ignited the fort's gunpowder storage, causing massive damage. The fort was repaired in the early 17th century. The Ottoman raid though, was avenged on the same year 1571 at the battle of Lepanto, where a trophy from an Ottoman gally, a figurehead named “The Beast”, was brought back to Hvar town. The Austrians, who became the island's rulers after Napoleon’s defeat, later added barracks and a new gunpowder storage room in the 19th century.

Descending the gentle switchbacks, we enter the older part of town within the medieval walls, where residences of Hvar's old noble families still stand. Beneath the Renaissance floors and cobbled streets there are once again traces of even older civilizations. Near the Porta Maestra, one of the medieval gates, archaeologists recently uncovered a Roman house. This was no simple abode – its affluence is made clear by the presence of mosaic floors and a hypocaust (the Roman underfloor-heating system). Several other excavation sites across Hvar town reveal ancient homes and graves, underscoring the town’s continuous habitation in some places dating all the way back to the first millennium BC.

The Grand Arsenal

Unlike Stari Grad which was established on the island of Hvar as a Greek colony in the fourth century BC, there’s no evidence of ancient Greek settlements in Hvar Town. The Romans were here from the second century BC, but after their empire's fall, historical records grow scarce until Hvar town reemerged in the 13th century as a key urban centre under the Republic of Venice. As a strategic stronghold within the Adriatic, the island of Hvar became the first stop for Venetian galleys crossing towards Greece, Constantinople and the Middle East. The wealth generated from this position is evident in the big urban projects still-standing today, such as the city walls from 1242 and the grand Arsenal, built after 1292, which served as a shipyard and a dry dock for the Venetian fleet.

The Venetian period also brought social upheaval. In 1510, tensions between the nobility and commoners erupted into a four-year rebellion. Rebels initially succeeded in expelling the nobility and seizing their wealth, but Venetian forces reclaimed the town after intense battles in 1514. One notable rebel leader, Matija Ivanić, escaped to Rome, leaving a legacy intertwined with local folklore.

The Church of the Annunciation of Mary and Hvar Old Town Square

One of Hvar’s most unique traditions arose from this turbulent era, now a UNESCO World Heritage event: the "Following the Cross" processions (Za Križen). As the story has it, after a secret meeting where the rebels swore over a crucifix to avenge the nobles' crimes, a miraculous event occurred: the crucifix in a small Church of the Annunciation of Mary began to bleed. The onlookers interpreted it as a divine warning against violence, which was heeded in a wave of public repentance and the first procession through Hvar’s town square. This marked the beginning of the processions, which have since become a tradition on the island.

After the 1510-1514 rebellion, the town endured further hardships, including the Ottoman raid of 1571 and the devastating lightning strike in 1579, leaving the island at a low ebb. But in 1611, Pietro Semitecolo, the Venetian governor, spearheaded a remarkable reconstruction, reviving Hvar within just two years. To symbolize the newfound peace, he established a public theatre above the Arsenal, just off the main square, bearing the inscription "ANNO PACIS PRIMO MDCXI" (“In the First Year of Peace, 1611”), still visible today. It still fulfils its intended role as a cultural centrepiece though centuries have passed and the world that made it has gone.

The Porta Maestra medieval gate

Hvar towns modern era began with the founding of the Hygienic Society in 1868, one of Europe’s earliest organized tourist societies. Supported by Empress Elisabeth of Austria, the society aimed to promote Hvar as a health resort, capitalizing on its mild climate and scenic beauty. This was just twenty-three years after Thomas Cook organized his first tours, marking the dawn of modern tourism in Europe. While Cook’s ventures catered to the emerging middle class, Hvar attracted aristocrats seeking therapeutic retreats. The Empress’s endorsement led to the construction of Hvar’s first actual hotel, which still bears her name. Island’s climate is still part of its appeal – it boasts the highest number of sunny days in Croatia, with an impressive 115 per year. As for hotels on the island, there is a fun tradition: when snow falls on the island—a rare occurrence—guests get to stay for free.

Today, Hvar town is a fantastically varied port of call with a broad range of ways to win your affections. The whole visual effect of the place is unutterably charming, and when you look closer, taking in the picture-book solidity of the fortress to Italianate houses and churches enfolded by the dotted greens of the hills and bathed by the pristine azure waters of the Adriatic, even the most demanding spirit will be given a boost. The town’s Venetian architecture and Roman underpinnings still stand as a testament to its past—one marked by conquest and survival, rebellion and revival.

Hvar Fortification Walls

If you’d like to uncover more of Hvar’s fascinating history, join us on our Cruising the Dalmatian Coast: From Dubrovnik to Split tour.

Leave a Reply