Not a great day: "The Last Day of Pompeii" as imagined in a 19th century painting by Russian artist Karl Bryullov.

On our historical tours you will hear many stories about the past. Based on rocks and walls and artefacts, these stories are nevertheless always about people.

That's the essence of archaeology: it is the study of past societies and people on the basis of their physical remains, namely the structures and buildings, the objects of daily life or works of art that they have left behind, for us to admire and enjoy, to puzzle over and to learn from. At the end of the day, what we look at and what we tell you about is all concerned with people; people like us, people who were born, lived and eventually died, people who strived and occasionally thrived, people who did great things and bad things and also mediocre ones, people who knew suffering and joy, success and failure, desire and disappointment, people who lived and loved.

Imagine losing - or mislaying - this fine object. The Morgantina Treasure is a key example of something going severely wrong for someone over two thousand years ago.

It is easy to forget this aspect: time strips away much, even most, of the recognisable individualism, the discrete identities of these long-gone people and their unique fates, leaving a more generic and more anonymous material record of their achievements and their failures. Our task is to bring them back, to repopulate the sites we visit with those people who created them and used them and made them what they were. The stories we tell you are about people: their lifestyle and activities, their beliefs and hopes, their tools and dwellings, their lives and their deaths.

That's all very serious, as it ought to be. Archaeology is, after all, a serious discipline within the humanities. But let's be a little more light-hearted: very often, the greatest things we love showing our guests, the very things that our guests enjoy and are amazed by, the things we are lucky to be able to share with them, are the result of someone a long time ago having had rotten luck, having gone through a bad patch, having experienced a time that wasn't their day, their week, their month, or even their year - not to mention their century.

This post is about instances when and where our greatest sites and items to show to and share with our guests are evidently the result of such misfortune, and of someone's loss, minor or major. It's often said that someone's loss is someone else's benefit. Here, we prove it.

A silver tetradrachm bearing the portrait of Alexander the Great, showing the king wearing a lion skin, attribute of the hero Herakles (Hercules). The image is a reference to Alexander's own claim of a divine lineage. (Numismatic Museum, Athens).

1. Losing a coin

It happens to everyone and it's annoying. Today, we mainly lose coppers. In antiquity, people occasionally lost bigger denominations and we benefit from that. Ancient sites, especially cities, tend to abound in lost coins. They are found trampled into the ground in houses, streets, squares and sanctuaries, or lost in wells or refuse pits, and they are ultra useful. Since coins, being state-issued currency, usually depict the current ruler or otherwise indicate who authorised them, they are an immense help in dating archaeological contexts. If a bunch of material includes a coin of such and such a date, we know it cannot have been laid down before that, helping us to understand the history of a place and its material.

Beyond that, all those lost coins are wonderful objects, testament to their era and often decorated with interesting and beautiful imagery reflecting the identity of the city or state minting them. The ancient Greek character who lost a tetradrachm (a silver 4 drachma coin, worth at least four daily wages at the time) or the Roman who mislaid a denarius (the common currency of the Roman Empire) must have been disappointed at least. On nearly all our tours, we get to see, analyse, explain and enjoy such coins in the various museums we visit. Bad for the persons who dropped them, good for us!

The Söke Tekkisla hoard, on display in the Museum of Miletus, was buried in a clay pot around AD 1580. It consists of 299 gold coins and 767 silver ones, including both Ottoman and Venetian issues.

2. Losing a lot of coins

Now, that's a different story. People hoard. Some people hoard odd things, like newspapers or pizza boxes, but the normal instinct is to hoard valuables. As antiquity had no reliable banking system, the old “under my mattress” (they didn't have a reliable mattress system either, alas) approach was common, as was the “under the floorboards” one. People would conceal or bury their collected savings in a safe place, usually in the form of a collection of coins, often in a clay or metal pot. When archaeologists find such hoards, it means that the person hiding them, presumably fearing some calamity, such as war, civil unrest or the tax collector, somehow missed the opportunity to recover them. Maybe they had to move elsewhere, maybe they had lost access to the space of hiding or maybe they had been killed by the anticipated trouble.

In any case, their loss is our gain: coin hoards don't only help us date contexts – they provide a perspective of what coins where circulating in an area at a given time, throwing light on the economy and exchange networks of the given era. Losing access to a coin hoard must have been a major bummer. Still, we profit from it when we find it – and not in financial ways (unless we're bad people): coin hoards (and other hoards of valuables) turn up on many of our itineraries in all three countries we travel. We're very sorry indeed, but we thank the former owner for the information he or she inadvertently left us.

A recreation of the Ulu Burun shipwreck from ca. 1,400 BC, its cargo of metal ingots and clay vases must have been missed by someone. Bodrum Castle/Museum of Underwater Archaeology.

3. Losing a ship

Alright, we can all agree that losing a hoard of coins is bad (unless it's the coppers you saved up for the arcade, in which case we don't care all that much). What about a cargo of items, such as important raw materials or impressive statues, being shipped from one place to another? Ancient shipwrecks are a wonderful source of information, because they are time capsules: everything on them was lost at the same time as one load. From the Bronze Age (1,400 BC) Ulu Burun shipwreck, a highlight of our visits to Bodrum Castle, which also includes the Classical (5th century BC) Tektaş Burnu wreck, via the Phoenician one on display in Marsala on Sicily to the Roman-era Antikythera wreck with its cargo of statues, now in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, in each case they tell us stories about the cultures, contacts and economies of their time.

Each of those discoveries is a major boon to our understanding of antiquity – and each of them must have been felt as a huge loss, to crew members, shipowners, merchants and everyone else involved, not least the crew members' loved ones. Much misfortune there, and our hearts might go out to these people across millennia - but still, we enjoy the fascination of such finds.

"Hermes holding the Infant Dionysos", by the Late Classical sculptor Praxiteles (before 350 BC). Discovered in the ruins of the Temple of Hera at Olympia, where Pausanias had seen it in the 2nd century, it is one of the few surviving original works by one of antiquity's greatest sculptors.

4. Losing a work of art

Art is tricky concept, actually, but it's been around at least since the ancient Greeks. Advanced societies develop first craft specialisation and then art, allowing certain individuals to achieve great skill in making objects that may not be particularly useful in practical terms, but that are admired for their perfection and their beauty and that end up being seen as key expressions of the era that produced them, resulting in great fame for both creator and creation. Sculptures and paintings are chief in this category and have been so for a long time. Most such art has been lost to them and to us, due to the usual ravages of time, to defacement, melting down, reuse and deliberate destruction.

Now and then, however, an ancient artwork, more rarely a very famous one, does survive. Often the shipwrecks mentioned above play a role, but now and then we even find such great works on land. usually, this is the result of accidents like earthquakes or other traumatic instances, causing a work of art to be inaccessible until the advent of excavations, for example as it was buried in the rubble of a collapsed temple, which is what happened to the Hermes of Praxiteles in Olympia. Another example are the abandoned marble kouroi in the quarries at Flerio on Naxos, left there as they were probably broken by accident during the process of extraction from the bedrock. We are so privileged to be able to enjoy such objects and we are eager to share them with you wherever we can - but what a loss they must have meant!

The extraordinary preservation of Ephesus, the splendid capital of Roman Asia, is due to the city's abandonment as a result of the loss of its harbour. Without its economic raison d'être, the city could not survive.

5. Losing an entire economy

I am writing this in Greece, so this entry suggests a whole range of poor jokes - let's avoid them. Economic failure is a terrible thing. But it can certainly be good for archaeology, and even better for sightseeing. Point in case: Miletus and Ephesus were the major port cities of ancient Ionia, the ancient region that is now the central part of Turkey's Aegean coast. In both cases, the city's role as a harbour was compromised by nature herself: the gradual build-up of silt (a nicer word for mud) caused by the very rivers that had initially bestowed them with their wonderful harbours led to an increasing distance between city and sea and more and more effort was needed to maintain the ports. Eventually, the cities lost their economic base and were abandoned.

As a result, we have access to vast ancient cities that have not been resettled in any major way at any point in time (unlike Rome, Athens or Istabul, cities that were in constant use) and that have escaped the fate of being used as quarries – and are thus virtually pristine, allowing a coherent and uncompromised experience of their millennia-old structure. Kaunos and Priene in Turkey, Morgantina and Segesta in Sicily, and Messene in the Peloponnese, as well as Gournia and Lato on Crete count among this list: their failure, abandonment and disappearance makes our guiding easier!

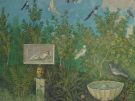

Pompeii is the best-preserved of all ancient cities, its streets and houses conserved by the very same ashes that ended its existence. Our opportunity to walk the streets and admire the homes of a 2,000 year old town is the direct result of a horrific catastrophe.

6. Losing a whole city

Paraphrasing Oscar Wilde, to lose one home may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose all of them looks like carelessness. That's rather unfair, admittedly. In very rare circumstances, an entire settlement, town or even city was lost in an instant, usually due to natural catastrophes, the kind of event that is as uncontrollable as it is unpreventable - and usually comes unexpected by humankind.

The two most famous examples of such loss, both of them among the most significant archaeological sites in the world, are on our itineraries. The more famous is Pompeii in Italy, snuffed out of existence by the eruption of Mt Vesuvius in AD 79, when this thriving Roman city was entirely buried in volcanic ashes and thus preserved for much later archaeological excavation and study. There are ancient accounts of the event, but we certainly would not need them to tell that the day of the eruption was a mediocre one at best for the Pompeiians, and not much better for their neighbours at Herculaneum, buried by mud-flows during the same eruption. In both cities, many inhabitants - perhaps most - lost their lives: not a great day for them - but a boon to archaeology: the discipline partially developed on its basis. In Akrotiri on Santorini, pretty much the same thing happened a little earlier. A little? Well, more like 1,680 years earlier, around 1,600 BC. We love showing you that site and the museum devoted to it.

Grave markers in the Kerameikos, the cemetery of ancient Athens, including the monument for Dexileos of Thorikos (394/393 BC). The effort made in commemorating the deceased often adds great information and great artistic achievement to our record of the past - as do the remains of the dead themselves.

7. Losing one's life

The ultimate loss is often seen as the ultimate misfortune, eclipsing any other loss one might suffer. That said, it's the only one of the losses in this list that is actually inevitable and universal. The misfortune here lies entirely in manner and timing. It is certainly true that the prehistoric warriors, ancient Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Crusaders, Normans, Arabs or Ottomans (and so on) whose lives and achievements we strive to understand and to share with our guests might have departed this life in more or less unfortunate circumstances – but even if they hadn't, it's safe to say that they would not be alive by now anyhow.

The death of others (and eventually our own) is the in-built loss that has driven much of human culture, religion, philosophy, art and so on, and that has inspired our desire to achieve something beyond our fated lifespan. That said, the human need to mitigate death has been an ultimate boon to archaeology. From pyramids to the Mausoleum, from sarcophagi to rock-cut graves and other burial monuments, from coins or jewellery to paintings, much effort has been spent throughout the ages on sending off our loved ones, revered ones or powerful ones in style and equipped with all manner of ostentatious or practical gifts to use in that next world - or maybe just to impress those present at the sepulchral ceremonies. Graves of all manner are a key source to archaeology, providing wonderful artefacts, works of art, weaponry, treasure and tools, but also throwing light on ancient beliefs and (on occasion) on the actual lives of the departed, through the study of their bones.

Leave a Reply