(The exhibition has been extended until January 17, 2021, and we have amended this post accordingly.)

The face of the Quirinal Boxer, a Hellenistic bronze statue, in its re-imagined coloured version, part of the Gods in Color exhibit. Note the different alloys used for his skin, hair, eyebrows, lips, blood and the haematoma under the right eye. The original is in the Museo Nazionale Romano in the Baths of Diocletian, Rome.

Gods in Color - Golden Edition awaits you in Frankfurt and it's worth adapting your travel plans for it!

A defeated boxer, seated in a tired and dejected pose, his muscles rippling, red blood streaming from the wounds of a recent fight, a purple swelling below his eye, and his blue eyes looking imploringly upwards - perhaps at the one who defeated him, awaiting some kind of judgement. A stately lady, wearing a pinkish-red woollen frock and a much lighter green cloak, the colours of the lower garment shining through the upper one where they touch. An archer, kneeling, tensed and poised to use his bow to make a kill, his legs and arms tightly covered in stockings and leggings, woven into a colourful pattern of red, green and yellow lozenges, with little shiny spots of gold sown onto the cloth. A stiffly posed female, the front of her saffron-coloured garment bearing a decoration, an embroidery, showing many tiers of fantasy animals in white on a red background, lined by green borders. A Roman emperor's face, vibrant with the colour of his skin, hair and eyes. What are these things I describe? Paintings? No - sculpture!

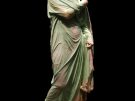

Statue of a muse from Delos, 2nd century BC, original and one of several suggestions for its painted appearance. The original is in the Liebieghaus's own collection, Frankfurt.

Let's assume you are interested in Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. It's not that big an assumption, considering you're looking at the blog of Peter Sommer Travels, a company specialised in cultural and archaeological tours and cruises, with a strong suit of itineraries in Greece, Italy, Turkey and other European countries. Of course, Greek and Roman sculpture (inextricably connected) represents a major feat in the history of human achievement, of art itself. Although it has fascinated travellers and scholars for centuries, there is still a lot to learn about this achievement, so rich in beauty and so broad in content.

If you are travelling through Europe (or in Europe) between now and mid-January of 2021, there is a very special treat available in Frankfurt (that is Frankfurt am Main), Germany. It is an opportunity to see Greek and Roman sculpture anew, to see it with the added perspective of colour, based on state-of-the-art research.

Another reason to visit Frankfurt: Botticelli's Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci (ca. 1480) at the Staedel.

Frankfurt - worth a stop

Let me digress for a paragraph or two.

Frankfurt is not normally on the list of top places to see in Germany for Peter Sommer Travels' guests (they tend to favour Berlin or Munich), although many of them travel through the city's airport every year. This is unfortunate, because Frankfurt certainly is an interesting place (note: I grew up there) and it features a superb array of museums, many of them lined up along the river.

Most famous among them is the Staedel, one of the country's finest collections of paintings. Nearby is the Liebieghaus, host to the exhibit I am writing about today, but also to a very well-curated permanent collection of sculpture ranging from antiquity via the Middle Ages to the Renaissance and Baroque eras. Other offerings include the Schirn exhibition space, which regularly hosts very interesting shows of international significance, and many more.

If your flight is through Frankfurt, you are well-advised to aim for a few hours between planes on any occasion - and even more so this year.

Coloured version of a portrait of the Roman emperor Caligula. First century AD, original at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

An important exhibit

What Frankfurt offers until late August 2020 is the most recent incarnation of Bunte Götter, the Painted Gods or Gods in Color (as it was called in the United States), one of the most significant ongoing projects in displaying ancient art.

The exhibit, based on decades of work by its initiators, Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, was first shown at Munich in 2003/2004. It has a simple premise: to explore the polychromy of ancient sculpture, the fact that all those statues, busts, reliefs and architectural decorations that we nearly always see in the white or beige or grey of the stone they're made of were originally painted, wholly or in part, and to make this phenomenon visible to the modern viewer, using full-sized copies of the ancient originals. When the original exhibit opened, and as it subsequently travelled the world to great acclaim (venues including Copenhagen, Rome, Istanbul, Athens, Harvard, Los Angeles, Berlin and Oxford), it tended to cause a bit of a stir wherever it went. Reactions often included terms such as 'dazzling', 'provocative', 'fascinating', but also 'gaudy', 'disconcerting' and so on.

The Copenhagen Caligula and three versions of what he might have looked like.

During its travels around the world, the exhibit has continued to ever expand its content. Since Professor Brinkmann moved from Munich to Frankfurt's Liebieghaus some time ago, that museum is now the home of the travelling exhibit: not its only venue, but its coordinating headquarters.

Polychromy - visible and invisible

The fact that ancient sculpture was coloured, its polychromy, has been recognised (often somewhat reluctantly) by scholars since the 18th century, when statues were discovered with obvious traces of paint on them. Considerable work was done to study the topic a long time ago, but it fell out of fashion early in the 20th century. There are many opinions on why that happened and why the image of ancient sculpture in its marble whiteness has dominated our view of ancient art for such a long time, including ones that have drawn much attention in recent years, linking the topic with modern ideologies. It is certainly worth considering all that background, because the question of why we see things the way we do is not unimportant. It's a discussion about us, our society, our aesthetic views and prejudices, and how those came to be.

The 'Chios Kore' from the Athenian Acropolis, c. 520 BC, preserves extensive visible traces of paint, permitting a detailed reconstruction. Original in the Acropolis Museum. (NB: the original is not part of the Frankfurt show).

I would, however, argue that it is as important to go back to the ancient works themselves and to try understanding what they initially looked like, how they were meant to be seen, what their creators had in mind (at best, we're a small part of that). That's what the Gods in Color project is about.

Inspired in part by the show itself, a vast amount of work has been undertaken in recent decades on this topic. Initially, it naturally concentrated on sculpture with obvious traces or shades of paint. A good example of this is the collection of Archaic statues from the Acropolis of Athens, damaged during the Persian sack of 480 BC and buried soon afterwards, thus preserving more original surfaces than works that stood in the open for longer. These pieces are now in the Acropolis Museum and the fact that they were once painted is still visible to the common visitor's naked eye.

An archer (so-called Paris) from the western pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina in full colour reconstruction. Note his Persian-style clothing, with leggings and a long-sleeved top, both bearing complex rhomboid patterns, under a waistcoat with images of lions and griffins. All this detail is invisible on the original, but was revealed by detailed 3D-scans. The golden dots are new in the 2020 exhibit. Original in Munich's Glyptothek.

Although there are numerous other such examples, the vast majority of ancient sculptures preserve no obviously visible traces of colouring. Sometimes, that is due to their long exposure to the elements, and sometimes to their treatment in the modern era: art dealers and museum curators often engaged in 'cleaning' ancient works, destroying what was left of the original surfaces. In such cases, only a careful study using various methods can reveal the traces of the lost colouring. This applies, for example, to the sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia on Aigina near Athens, now on display in Munich, which triggered the original exhibit and remain one of its highlights.

Multiple methods

Much is now being done to study the paint on sculpture, not just in Munich or Frankfurt, but also in Greece, Italy, the United States and many other places. It has become a distinct field of scholarship and research and it uses any available analytic technique, from oblique lighting via ultraviolet lighting (recently UV LED lighting) and X-ray fluorescence to 3D-scanning (which can reveal minute variations in a statue's surface), chemical analysis and others, all aiming to find the remotest traces of colouring on the ancient works, even where none of them remain visible to the human eye.

Other sources on the use of colour in antiquity include painted architecture, such as the façades of Macedonian tombs, the most famous being that of king Philip II at Vergina/Aigai (Peter and I were there just a few days ago!).

Scholars also make use of other ancient sources, among them textual descriptions and analogy with other media in ancient art, such as terracotta figurines, another medium in three dimensions that very often preserves paint extensively, but also two-dimensional media such as fresco painting.

An impressive display

That's the scientific aspect, but it's the museological one that makes Gods in Colour such a special experience: the project uses full-size casts or 3D prints of the ancient works to recreate the colouring by painting them directly with materials similar to those used in antiquity. More recently, it also projects versions of colouring onto the original pieces (this is used to great effect in the Frankfurt exhibit on a single piece, a muse from the Liebieghaus's own collection, shown further above, offering different versions of its initial colouring). The results are stunning, sometimes indeed jarring at first sight, but always revelatory: they may not change the way we see ancient sculpture (because we are what we are), but they do change the way we understand how it was meant to be seen.

Colourful masterpieces in stone...

Coloured reconstruction of a battle scene on the Alexander Sarcophagus from Sidon (Lebanon). Late 4th century BC, original in Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

If you have seen the exhibit in one of its earlier showings, you will meet many old friends in the 2020 version (it comprises over 60 reconstructed pieces, nearly twice as many as it did in the same museum a decade earlier). The archer from Aigina (see further above) is still here, so is the Peplos Kore from the Acropolis (see below) and so is the Alexander Sarcophagus (see just above). That said, they may not look quite like they did in the previous versions shown: the exhibit is an ongoing process and it is also, and always will be, to some degree speculative. No matter what detail extra analysis reveals, we cannot be quite sure what these pieces looked like when fresh, so the exhibit offers evidence-based possibilities or suggestions, but not certainties.

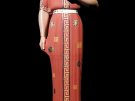

The Small Herculaneum Woman, probably from the 4th century BC, was often copied already in antiquity. The Gods in Color reconstruction is based on a 1st century AD Roman copy now in Dresden for the cast, and on a 2nd century BC Greek copy from Delos, now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, for the traces of colour.

To exemplify such a change: the archer from Aigina with his Scythian-style stockings and leggings and their lozenge patterns is now enriched by little golden flecks at the centre of each lozenge (see image further above). This addition is based on two sets of evidence: on light spots emphasised in Greek vase paintings that show such foreign wear, and on golden appliques sown to the actual garments of Scythian archers, preserved in tombs in Ukraine and neighbouring countries. It's a fairly subtle change, but it does affect the overall appearance of the reconstruction considerably, adding a very striking additional visual focus. The same idea has been applied to many other pieces, giving the exhibit its current byline: Golden Edition.

There is also much completely new material. The Small Herculaneum Woman, a Late Classical or Hellenistic sculpture (4th or 3rd century BC) that only survives in copies, is here, based on the famous example from Delos in the Cyclades that now resides in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens (incidentally, she's typologically connected with the Lady of Kalymnos, a piece we have discussed on this blog). The Gods in Colour, working from subtle traces on the Delos piece, gives her a pink undergarment and a green one above, and a way of the pink shining through in certain places as she is tightly wrapping herself in both. The effect is surprisingly realistic and devastatingly sensual. Both realism and sensuality were already key features of the work in its 'unadorned' marble form, so the coloured version does not divert from the statue’s evident characteristics, but emphasises them further, which is what makes it compelling.

Coloured version of a kouros from Tenea, ca. 560 BC. Original in the Glyptothek, Munich.

New coloured reconstruction of the kore of Phrasikleia from Merenda near Athens, ca. 540 BC. Original in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

The same can be said for a wonderful kouros, that typically Archaic (6th century BC) image of the nude young male, somewhat stilted or stylised in position, based on one now in Munich. His flesh colouring adds surprising liveliness and vulnerability to him, as do his navy blue eyebrows and the carefully combed star-shaped hair (?) around his nipples and pubic area. An extraordinary sight of well-groomed male beauty, he adds a dimension of detail to the bare stone version, all based on careful study of the original piece! His near-contemporary, the famous kore (a female Archaic statue) of Phrasikleia from Merenda near Athens, by the sculptor Aristion of Paros, is also here in new glory, with a gilded lotus crown and belt, and a red dress decorated with ornaments in both paint and metal.

... and in bronze

A coloured reconstruction of Bronze B, one of the two famous Riace Bronzes, using coloured bronze alloys for body and hair, and suggesting a silver alopekis, a fox-skin cap. Original in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Reggio di Calabria.

A recent focus of the Gods in Colour project and its collaborators has moved beyond stone sculpture to bronze. It has long been clear that ancient Greek hollow-cast bronze statues used different alloys to emphasise features like lips, hair, nails, teeth and so on, not to mention added detail in other materials, notably the eyes. This is clearly visible in famous masterpieces like the Delphi Charioteer or the celebrated Riace Bronzes in Reggio di Calabria (if you have not seen those, you need to change that!). The Frankfurt exhibit includes full colour reconstructions of the two Riace warriors, based on a very careful study of the originals. It also proposes an answer to the long-standing problem of the missing head-dress of warrior B, compellingly suggesting the most surprising of all: a silver version of a hat made of a fox scalp, a typical attribute of Thracians in Greek art. Arising from this, there is a new interpretation of their origins (spoiler alert: it suggests they once stood on the Athenian Acropolis), and their meaning (it suggests they are the Athenian king Erechtheus and his Thracian adversary Eumolpos, thus illustrating a legend associated with the city's early history).

The two Quirinal Bronzes interpreted as a group depicting Amykos defeated by Polydeukes. Originals in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome.

In the same breath, the exhibit also attempts a full-colour reconstruction of two other famous bronze statues, the Resting Boxer and the Hellenistic Prince, discovered together in 1885 in the ruins of the 4th century AD Baths of Constantine on the Quirinal Hill in Rome. The boxer is definitely Hellenistic and was at least 500 years old when it was placed in the baths, whereas the date of the ruler is disputed. Hitherto, they were seen as unrelated by most (but not all) scholars, but the new study triggered by the reconstruction suggests they belong together, showing an episode from the myth of the Argonauts' voyage: the defeat of the Anatolian king Amykos by Polydeukes (Pollux), in different versions ending either in the former's execution or his merciful and civilising punishment. Irrespective of that interpretation, the coloured reconstructions are fascinating. The boxer, with his brightly coloured leather bandages serving as gloves, his red streaming blood mentioned at the beginning of this text and his fearfully expectant eyes, is realistic in his despondency and exhaustion. His conqueror (if that's what he is), in the elegant pose and fitness of the young hero and the arrogant but thoughtful expression of the judge, is humanised by the coloured alloys adding realism to his figure. Together, they are a feast for the eyes.

New interpretations

Original and coloured reconstruction of the famous Peplos Kore from the Acropolis. The colour reconstruction of her clothing suggests that she is the cult image of a goddess, most likely Artemis, thus holding a sword or bow. Original in the Acropolis Museum, Athens. (NB: the original is not part of the Frankfurt show).

This pattern, where the study of a well-known piece focusing on its colouring leads on to a reconstruction of various attributes and then to a reinterpretation of the work, also applies to one of the most celebrated marble sculptures from the Acropolis of Athens, namely the Archaic Peplos Kore (circa 520 BC). It has been clear for a long time that the garment she wears is not actually a peplos, and it has always been visible that it bears intricate figural painting at the front. Although she has been part of the Gods in Colour exhibits since its very beginning, it is in the current version that an important reinterpretation of the piece, based on much scholarship, is presented. The ultra-ornate garment she wears has no parallel among the Archaic female statue type known as kore. For most of these images of girls or young women in their finery we have no means to know whom they depict: mortals, heroines, goddesses? The Peplos Kore's specific garment, however, appears to be an ependytes, a type of attire only known on deities, and with its animal friezes specifically on Artemis (and especially the famous and very strange Artemis at Ephesos/Ephesus). Following this argument, the statue ought to be Artemis herself, and it can further be proposed that the missing objects the statue once held in her hands were weapons, most likely a bow, the goddess's most common attribute or a sword.

A lot to see and to consider

Coloured reconstruction of the head of a warrior from the eastern pediment of the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina near Athens. Original in the Munich Glyptothek.

There is much more to discover in the exhibit, and a good place to start is the excellent website that accompanies it and explains many of the underlying concepts and methods, with superb illustrations, some of them interactive.

In conclusion, what Gods in Colour has to offer, again and again, is a new look at ancient sculpture, a new way of appreciating and understanding these works, sometimes shocking, sometimes revealing, sometimes provocative and sometimes helping us to make sense of a work. It is fascinating to trace the different methods used by scholars and to virtually look over their shoulders as they propose versions of a piece. Of course, it is also thought-provoking to see how a new look at this one aspect of an ancient and much-discussed work can throw open new interpretations of its meaning. That said, the exhibit is not devoid of controversy: much as the polychromy of ancient sculpture is now accepted, there are differing views on what the colours looked like, how dominant they were, and so on: the Gods in Color approach is often accused as brash and simplistic. But it's a start...

Time to see ancient polychromy - at the exhibit or on your travels

The current exhibit, Gods in Colour - Golden Edition, is open at the Liebieghaus (except Mondays) until August 30, 2020. The exhibits are well-labelled in both German and English, and the excellent audio-guide, offering much additional detail beyond the labels, is available in German and English (in English also as a smartphone app - I highly recommend this for those who won't make it to the exhibit itself). The exhibit is further accompanied by a lavish catalogue with countless illustrations, currently only available in German (but I am sure that a new English version will eventually appear during future showings - the last complemented the 2017/18 showing in San Francisco and is currently out of print). in practical terms, you can reach the Liebieghaus from Frankfurt airport in a bit over half an hour by public transport, or 15 minutes by taxi. A full visit of the Gods in Color takes about two hours.

Detail of the kouros shown further above (if you are viewing this on a smartphone, turn it sideways).

So, a stop at Frankfurt is well worth considering. Otherwise, you can see the originals of many of the pieces presented by Gods in Color and much other material relevant to the topic of polychromy during or in conjunction with many of Peter Sommer Travels' tours, especially in Rome, in Athens (where the Acropolis Museum also has exhibits dedicated to the topic), or in Thessaloniki, but also in Istanbul, Naples, Siracusa, Reggio di Calabria, London and many other sites on or conveniently near our itineraries. As always, our expert guides will be happy to tell you more about this extraordinarily fascinating topic.

A feast for the eyes in Living Colour!