What exactly do you see? A tent-shaped wooden container (the wood is yew), about the size of a small suitcase in modern terms (it's 48cm or 19" tall), all four visible sides of it adorned with metal decorations, cast in bronze, gilded, incised and attached to the wood with nails or dowels. There must once have been more of these metal adornments, as indicated by the obviously incomplete compositions and the many holes in the wood.

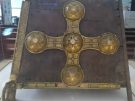

The best-preserved side of Saint Manchan's Shrine.

The best-preserved composition, on one of the wide sides, shows human figures arranged around a large central cross. The cross is decorated with large hemispherical bosses at its centre and four terminals, decorated with very intricate interlace, a pattern of intertwined strands, some of them terminating in stylised animal heads, tails or limbs. Most of the flat fields between these strands are filled with geometric patterns and fields of yellow enamel. A similar cross is on the 'back' of the container, and dowel holes indicate that there must once have been figures here as well. Panels with similarly complex interlace patterns are attached to the triangular narrow sides of the wooden container. Bands with more interlace do (or did) adorn the object's edges, and large metal rings are attached to three of the object's four short legs.

The six remaining figures on the left-hand side of the cross.

The eleven human figures, arranged in two rows under the arms of the "main" cross, are very intriguing. They portray a series of men, all of them bearded, some also with moustaches. All are wearing long kilt-like garments, with patterns shown, and on all of them hair or a head-dress is indicated, in one case apparently a helmet. Two of them hold short staffs in their right hands, and one each an axe, a sphere or ball and a rectangular object, most likely a book. Additionally, one appears to lack an arm, two have their hands folded, one is showing his left palm to the viewer, and one is pulling his own (forked) beard with both hands.

Using my archaeologist's or art historian's eye, these figures remind me of small-scale sculptures belonging to the Romanesque art of the European continent (especially France and Germany), which thrived in the 12th and 13th centuries AD. The interlace patterns on the crosses and side panels, however, bear elements of the Celtic tradition that developed in continental Europe in the final centuries BC and prevailed in Ireland for over a thousand years, but also of the 11th century AD Scandinavian "Urnes style" in metal or woodwork. In other words, the overall object would be a confusing one if it had no context.

One of the sides of the Shrine, with more interlace.

Well, it does. It is locally known and revered as "Saint Manchan's Shrine", and the fragments of human bones contained in it are believed to be those of the Saint, making the object a reliquary, a container for holy relics, and by far the most elaborate example of its kind from medieval Ireland. The rings at the feet were used to help carry the shrine in processions.

Saint who? Early Medieval Irish historical texts and local traditions name many obscure saints, including no less than five Manchans. The one referred to here ought to be Saint Manchan (pronounced Mawn-e-chan) of Liath Mancháin or Lemenaghan, an early monastery that bears Manchan's name and lies only a few miles away from Boher. We know very little about Manchan's life, but according to tradition, he was a monk at Clonmacnoise, 17km (10.5mi) to the west, became the founder of the aforesaid monastery in AD 645 and passed away there in 661 or 664, thus becoming the revered patron of his foundation and by extension the patron saint to the surrounding region.

Manchan's other claim to fame is a lovely short poem attributed to him. In it, he asks the Lord to provide him with a place to found a monastery. It begins thus: O Son of the living God, ancient eternal King, / Grant me a hidden hut to be my house in the wild, / With green shallow water running by its side / And a clear pool to wash off sin by the grace of the Holy Ghost. / A lovely wood close by around it on every hand / to feed the birds of many voices, to shelter them and hide... Linguists place its original language, a form of Old Irish, somewhere between the eighth and tenth centuries.

The 'rear' part of the shrine, with an even better-preserved cross, but no remaining figures.

Two physical items associated with Manchan survive today. Firstly, the remains of Lemenaghan monastery do exist and may well indicate a date as early as the seventh century. Secondly, there is our shrine, holding his mortal remains. Apparently, it was kept at the ruined monastery until the 19th century, when it was moved to Boher.

The shrine is clearly much more recent than Manchan's life. Comparison with other items of known date would suggest that it was made around AD 1130. It is an example of the finest craftsmanship available at the time, when Ireland was a fragmented country of many petty kingdoms and when art was the reserve of monasteries. It must have been made at one of the most important monastic centres in the country, most likely at Clonmacnoise. We have no idea what might have occasioned the manufacture of a new receptacle for the saint's real or purported bones nearly four centuries after he died. The shrine's extraordinary craftsmanship means that it and its contents must have been considered of great importance. Maybe the commemoration of Saint Manchan had its role to play in the complex political network of religious and tribal power that dominated Ireland at the time.

A detail of the insanely complex interlace on the side panels. Note the animal head on the central bar (bottom left) and those on the interlaces themselves.

There is another possibility. The Annals of the Four Masters, one of the most important sources for medieval Irish history, contain a very suggestive entry: AD 1166, The shrine of Manchan of Maethail was covered by Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, and an embroidering of gold was carried over it by him, in as good a style as a relic was ever covered in Ireland. This might well describe the shrine at Boher, but the date is a little later than we should expect, and Manchan of Maethail (now Mohill) is a different saint, associated with Mohill in county Leitrim, 68km/42mi to the north. Could he and Manchan of Lemenaghan have been conflated or confused at some later point, leading to the placement of the former's relics in the latter's church?

Be that as it may, what about the Shrine's iconography? The two large crosses are straightforward, they are the supreme emblem of Christianity, and in Irish medieval art they turn up in many elaborations. The Celtic/Scandinavian interlace is also standard at the time, a fusion of two long-standing cultural traditions that had merged into a new whole, its tradition going back to the illuminated manuscripts and the High Crosses of the previous three or four centuries. The human figures, by themselves, also fit well into the art of their time. What makes the Shrine of Saint Manchan so unique is the preservation of the object and its ensemble of motifs.

The five remaining figures on the right-hand side of the 'main' panel's cross.

As regards the human figures, they are wonderfully mysterious. Whom are they meant to depict? There are only eleven of them now, but the dowel holes and spacings would indicate there may once have been nearly fifty of them. It seems clear that these are not random human figures, that they carry some specific meaning or narrative: the craftsman who made them knew whom he was meant to depict, the intended viewer would recognise them, and they were appropriate for the twelfth-century commemoration of a seventh-century saint. Unfortunately, that meaning is not accessible to us now; there is no medieval story or list or account that helps us define their identities. They might be local rulers, clergymen or saints, characters from the bible, from Irish or Norse legend or all three, personifications of theological concepts, or even images of personalities that played a role in the saint's now mostly-forgotten life.

The Boher church has fine stained glass windows by Harry Clarke, from 1930. One depicts the Shrine itself, fancifully re-imagined in its original completeness.

It is fairly typical for a local area in Ireland to (fervently) worship an obscure local saint, usually not officially recognised by the Roman Catholic Church, but associated with the surrounding region. It is not typical, however, to find a 900-year-old treasure on display in the local church. The people of Boher are clearly well aware of their luck and very proud of it: the shrine is a central motif on the wonderful stained-glass windows by the renowned Harry Clarke of Dublin, installed in 1930. You can admire the Shrine of Saint Manchan for yourself, along with many more wonders, on our tour Exploring Ireland: the Heart of the Emerald Isle.

Leave a Reply