Visage of a masked ‘cavalry sports helmet’, from the fort at Ribchester, Lancashire, late first to early second centuries AD.

The Roman army is one of the reasons I’m sitting here writing this. As a child living around the fringes of army bases that sort of topic was always going to be interesting, and it became one of the ways the ancient world first got its hooks into me: a fort-gateway drug, if you will. I was helped by school libraries having Peter Connolly’s books with their superb paintings which I’d endlessly try and copy: I can still close my eyes and summon up his fight around the siege engines at Jerusalem, and his pursuing cavalrymen after the Battle of Cremona. Interest in soldiers became an interest in ancient history and broadened to include as much about it as I could possibly absorb. So, while the Roman army didn’t remain my sole focus, I’m definitely a target audience for this exhibition and may have made noises audible only to dogs when I first heard it was to happen.

Fragment of a relief from a mausoleum showing legionaries in battle-formation, early 1st century AD. From Glanum, St-Rémy-de-Provence, France.

So does it match up for me, and is it still worth seeing for people who inexplicably manage to go for hours without cohorts on their mind? Absolutely yes on both counts. There are some minor quibbles which we’ll get to, but they shouldn’t stop you: everyone should find something of interest here, and if you’ve an even passing interest in the Roman army, it’s pretty much essential that you go.

I had one obvious question as soon as the exhibition title was announced, because it struck me that even the British Museum would have trouble mounting an exhibition of legions alone from its own material and what it could obtain by loan. Of course the Roman army was made not just of the high-status legions - Roman citizens when they joined the army - but, among others, also of auxiliaries (non-citizens, but from the peoples within the Roman empire) and naval troops. Very sensibly, despite the title, these are included, which means we get to see some of the most famous pieces drawn from Hadrian’s Wall, the Antonine Wall and Egypt. In fact, one of the conceits of the exhibition is to follow Claudius Terentianus, whom we know about from a second-century family papyrus letter archive in Egypt; he served first with the ‘marines’ and then graduated to the better-paid, more prestigious legions after some deft greasing of networks and palms.

Silver bust of the emperor Galba looking rather Brando-in-The Godfatherish, AD 68-69; from the House of Galba at Herculaneum.

For the exhibition, it’s a good device to make those unaware of the different branches get the idea, and to begin to see the ramifications of having these different types of service. Now, while this broader approach would have made it easier to mount the exhibition just from what’s to be had in Britain (museums on Hadrian’s Wall, the Antonine Wall and Colchester are all well represented), the British Museum has once again benefitted hugely from generous loans by institutions in Germany, France, the US and Italy. The amount and quality of material which anyone with an interest in the Roman army will be able to tick off their bucket list is very impressive; no: staggering. Few would have the resources to go and hunt down all these objects in so many different locations. Flicking through my old Peter Connolly book, young me was able to cheer over and over again at the appearance of things he’d finally got to see that he never expected to.

Portrait head of the empress Julia Domna, marble, probably from Rome AD 203-217 © Yale University Art Gallery, Ruth Elizabeth White Fund.

How does it all work then? The arrangement adopts an approach that isn’t exactly novel but is a pretty sensible one that breaks things down for the new viewer and ticks off most of what you’d expect to find in an overview. Essentially the exhibition is organised around the ‘life cycle’ of a soldier, so we get recruitment, training, camp life, musicians and standards, ancillary services (blacksmiths, food supplies etc), weapons armour and battle and then the majority of the other topics we’d expect: the wider role of soldiers such as in keeping civil order and ‘policing’, life off-duty (gaming, bathing and the like), families (wives and children, the folks back home), slavery (soldiers both owned slaves and took slaves on campaign; both are touched on), the legal rights and privileges of soldiers and, finally, retirement. This is accompanied by backdrops that vaguely suggest a camp’s street as you go up the main lateral of the exhibition space, with a hint at a barrack block off to one side.

Don’t ask me to talk about highlights. I mean, I will – but only if I can stress that these will be very different depending on your interests and where you’ve been before. So, for example, if you’re one of the wise people who’ve joined us on Hadrian’s Wall, while you will love the material from there and happily recognise it, finds newer to you may be more exciting. For those who haven’t been to Vindolanda, say, the organic remains and writing tablets will be particularly breath-taking.

Tombstone of Regina, the freedwoman and wife of Barates of Palmyra, from outside the Roman fort at South Shields (Arbeia), just south of Hadrian’s Wall; second century AD © TWCMS

Those who’ve come for ‘army’ as much as ‘Roman’ will have an absolute feast: this is one of the best touring gatherings of armour, weapons and famed tombstones of soldiers wearing them likely to happen. But there is far more to the exhibition than that. All soldiers spend most of their time not fighting, but bored or in drudge work; and then there are their families, legally recognised or not, and those around them – civilians or the conquered - affected for good or ill by the dropping of hundreds or thousands of men representing an imperial power into their vicinity.

For people coming to this topic anew there will be surprises, I think. Surprises firstly in the scope of what we can study about this institution. Not just wars and battle tactics. These new viewers may be surprised to learn how difficult it could be to get into the army, especially the legions. The need for certain physical characteristics, and even letters of recommendation – I expect people will be struck to discover some of these still exist and can be seen and read. Training you probably know about, but what archaeology can bring us given the right conditions is also pretty mind-blowing, as shown by one of the ox-head archery targets from Vindolanda, pock-marked by dozens of arrows shot into it, or the vaguely anthropomorphic and man-sized wooden target from Carlisle. Those same conditions give us a pretty sizeable spread of an army tent, and even wooden tent-pegs. For different reasons, Egypt’s different conditions gives us items whose survival really does astound, like the red woollen sock with its separate toe, just under a couple of millennia old.

Vindolanda’s writing tablets are here, represented by some of their most famous examples including the Sulpicia Lepidina birthday invitation, with what is probably the first writing by a woman in Britain, and the Brittunculi tablet, dismissive of the ‘little Brits’’ martial abilities. I suspect you’ll also find the modern look of the medical instruments fascinating, especially given the compartmentalised little bronze box some of them were found in. In this less directly warlike category, particular standouts for me were the dice-tower, shaped like a small latticework siege tower, designed to obviate gaming shenanigans with loaded dice; it’s something I’d first read about when working on my doctorate, and here I was looking at it; and then a chunky gold ring proclaiming its owner to be a custos armorum in charge of the armoury of Legio XXII Primigenia. A man evidently proud of his position.

Painted Roman scutum, third century AD, from Dura Europus © Yale University Art Gallery

The army’s place in the empire is partly dealt with in connection with, who else, Septimius Severus - the emperor who on his deathbed advised his sons to stick together, pay the soldiers, and ‘sod the rest’. So we see loyalty expressed in the images of emperors on standards – an amazing survival – and the truly exceptional staved-in large silver bust of the Emperor Galba from Herculaneum. The emperors, you come away aware, were quite determined to know the question “you and whose army?” could be safely answered. Loyalty wasn’t just welded by the emperor himself: we know of several empresses with the title mater castrorum (‘mother of the camps’) expressing their caring relationship with the troops; and given the occasional propensity of soldiers to soppiness, it’s likely to have been quite effective. Prime representative of this at the exhibition is Severus’ wife, Julia Domna, with her instantly-recognisable melon-hairdo (mind you, the exhibition’s suggestion that this coiffure slightly resembles an army helmet did make me don my sceptical face, and would probably not have been the best response on her return from the hairdresser’s tender ministrations).

Bronze helmet (with modern replica cheekpieces) from the River Rhine near Eich, Germany. As we can see from the punched detail on the neck-guard, it was owned by Marcus Arruntius from Aquileia near later Venice who served in the century (80-man unit) of Sempronius. (Private collection, image ©British Museum)

At the exhibition’s far end, have another famous woman with a royal name, if not status: Regina on her tombstone from South Shields (a site we visit on our tour), one of the finest pieces from Roman Britain. Wonderful to see, but also a good example of the social impact of the Roman army: though depicted as the epitome of staid Roman matronhood, she had been a slave with an implied origin in Essex or Hertfordshire, freed by her master – who in turn was from Palmyra in the Syrian desert and had some connection to the army - and then married to him. Neither was Roman in origin yet everything proclaims their Roman-ness (nearly everything: when you go, look below the Latin inscription to see what I mean).

The only topic that did seem to me to be largely missing, and it is a large one, is religion. The eclecticism of Roman military religion is a major sphere of study, and its absence was a surprise, but you can go and find out more about it in the museum’s Roman Britain gallery, or come to Hadrian’s Wall if you want to know more.

Gilded-bronze draco-standard, about AD 200, Niederbieber, Germany © Landesarchäologie Außenstelle Koblenz

Well, then, its an exhibition about more than arms, armour and war. But given its subject, those are going to be important and there’s a really impressive array of big hitters here, some of the most famous objects from the entire empire. We have some magnificent tombstones depicting soldiers, including the famed centurion Facilis from Colchester, and Marcus Caelius who was killed in the Varian disaster, in his case a cenotaph since his body was not recovered (this is a copy, but a good and imposing one). We have cavalry trappings which seem to name the owner as serving in the unit of Pliny the Elder, more famed for his writing career and eventual death in the eruption of Vesuvius.

Then we turn to an object that for me is worth the entrance alone: the exquisitely painted shield from Dura Europus on the Syrian frontier, a vanishingly rare survival (missing its metal boss, but nicely paired with the similarly highly-decorated bronze boss from the mouth of the Tyne – both, I note in exactly the same arrangement as they appear in Peter Connolly’s painting: an ‘easter egg’ for afficionados?). We have a row of swords and helmets which show us that the Roman soldier’s appearance – and fighting techniques – did not remain static for two centuries. This begins with a so-called ‘jockey cap’ type helmet which I’d need some persuading to believe was worn by a Roman soldier; it’s always, I think rightly, been displayed in the Iron Age Britain galleries. But it illustrates an important point: the Romans were very happy to take inspiration and models from their opponents and run with (charge with!) them, so we can see how much Roman helmet design took cues from the Celtic world.

Second/third century iron horse armour for a cataphract or clibanarius (heavily armoured horsemen with lances; think roughly of a mediaeval knight) from the Roman fort at Dura Europus on the Syrian frontier. © Yale University Art Gallery, Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos.

Next to these are the famous and distinctive hooped, banded cuirasses of Roman armour now known as lorica segmentata, not only the Corbridge cuirass, but Newstead too. Amazing. You’ll find parts of catapults, pilum-heads an actual [!] draco (the dragon head from one of the cavalry standards with a tail that would flutter in the wind of the charge) and a whole series of cavalry mask-helmets with their alienating, impassive visages. The Ribchester one takes the prize for me; others will be excited to see the relative newcomer, the Crosby Garrett helmet, unearthed from Cumbria as recently as 2010. And then you can move on, noticing what looks out of the corner of your eye in the dim lighting like, what? A log?

Lorica segmentata cuirass from the Varus Disaster battle-site at Kalkriese, north-west Germany, AD 9 © Museum und Park Kalkriese.

And then you look properly. And, in my case, sotto voce, you say “no way!” because you never expected to see the great scaled horse armour from Dura. You’d seen it in old black-and-white photographs by the original Yale team, and painted reconstructions, but here it is, scales delineated by atmospheric shadow and entirely splendid.

And that doesn’t complete the grin-inducing elements on this score, because there’s a select but brilliant cluster of material from Kalkriese, the – or a – site of the Varian Disaster, the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest in AD 9 which so shook the Emperor Augustus. Again, these are some of the pick of the crop: a shackle for prisoners, another lorica segmentata cuirass (an important one, because unexpected: we use to think this form of armour developed later, but here it is, firmly in the early rather than mid first century AD) and then one of the things I’ve most wanted to see and hadn’t known would be here, so a wonderful surprise.

Bronze mule or donkey bell from the Varus battlefield at Kalkriese, AD 9; it was found stuffed with grass.

The donkey bell.

One of the archaeological finds that I find most pregnant with meaning. For it was found stuffed with grass to stop it making noise. By this time, the men of Varus’ three legions, Marcus Caelius perhaps then still alive among them, knew they were in deep trouble. Let there be silence while we wind down the miles to safety. Let us gain a little time before they know we’re moving….

All to no avail.

A small thing, smaller than I expected. Possibly my favourite thing there.

Crocodile skin used perhaps as armour, though alternatives have been suggested (religious use?), Manfalut, Egypt, third or fourth century AD © British Museum

So far it’s been an excellent exhibition, but I did say there might be some gripes, so let’s get them out of the way. Now, to be clear, none of these should stop you going. So; firstly the lighting is pretty low, and I don’t think that’s all due to the presence of ancient leather and papyrus, since it’s increasingly common in displays, and BM exhibitions. It makes occasional details difficult to see, especially when the lighting that there is takes the form of pinpoints which don’t always illuminate in the best way and also make it harder to see through some of the glass which is (a bane of my museum life…) far too reflective.

Some of the space could perhaps have been better used to spread people around a bit more now numbers seem well and truly back to those before the pandemic: it would avoid pinch points and looking at objects with a press of faces behind them on the other side. One or two items could have been shown to more advantage – the Lugdunum burial for example might be easily missed, and a few would have been better at different heights. All of these grumbles are things that could have made a very good thing better, so let’s not obsess about them.

Instead let’s take our leave by saying goodbye, as the exhibition enables us to, to some of these soldiers and those they impacted, because we should always remember that these objects are interesting because of the stories they tell of lives. Some of these men, and their endings are very immediate as we pass through the exhibition, and form some of its cornerstones. Early on, we have the Roman soldier from Herculaneum, killed horribly in the Vesuvian eruption, laid flat on his back, arms pugilistically raised, with his weapons and equipment around him; we have two more skeletons seemingly buried illicitly in Canterbury in the second century, both probably soldiers, one originating from as far away as east central Europe; killed and dumped with their swords in what seems to have been an unmarked grave.

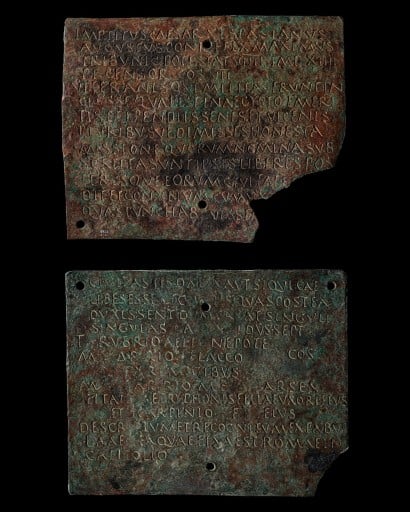

Bronze ‘discharge’ diploma of Marcus Papirius of Arsinoe in Egypt, a rower in the Alexandrian fleet for 26 years, dated 8 Sept AD 79, granting rights of citizenship to himself, his wife Tapaea and their son Carpinius. From Egypt. © British Museum

Next to them is the recent discovery of the skeleton of a crucifixion victim from Cambridgeshire, the remnants of a nail still in his ankle, his death likely overseen by soldiers. Finally I pause not at a body, for that is gone, but the leavings of one. This is the Lugdunum soldier I mentioned a little earlier, fairly certainly killed in the vicious battle that took place there in AD 197 between the forces of Septimius Severus (Julia Domna’s husband) and the Roman army of Britain, vying for empire under its governor, Clodius Albinus. Roman soldier fighting Roman. We know Severus won; our man here, girdled with a fine belt on which were bronze letters ironically making the popular phrase felix utere (‘use luckily’) did not. For me, this was another particularly striking encounter that I’d long looked forward to.

Gaming board for the bandit game, ludus latrunculorum, from Vindolanda, Northumberland © British Museum

Last of all I’ll mention the ‘diplomas’, the bronze documents recording, in beautifully flowing letters, the arrival of auxiliary soldiers at the end of their official term of service and thus a grant of citizenship. There are several of these scattered around the exhibition, and they are among the finest you’ll ever see. And they remind us that for all the years of toil and mind-numbing fatigues, for the times when that was punctuated by battle and fear and friends lost, and maybe regret over punishments administered and lives ruined, there would also be memories of dice games in bath-houses, friendships and perhaps marriages (think of Regina) made for these soldiers to take with them along with their tidy pension, discharge money and the diploma that proved they were now a Roman citizen, no mere provincial; Latin speaking, with new rights and expectations. It’s worth ending with that thought: that the Roman army was an engine for far more than just conquest.

Catalogue

The exhibition is accompanied by a handsome, if pricy, book, though it’s really more a “book to accompany the exhibition”. I do rather miss the existence of a traditional catalogue. Most people will absolutely prefer this as a readable introduction without overly-academic articles (albeit occasionally in need of an editorial and fact-checking eye); it just makes it a bit less useful for those with more scholarly interests.

Interested in the Roman army or the wider Roman world? Why not take a look at our Exploring Hadrian's Wall or Exploring Rome tours?

Or you can see our full schedule of expert-led archaeological tours.

Leave a Reply