"Another view" is an occasional series of posts presenting the sites and areas we see on our travels through the eyes of writers. From the great ancient sources via travellers of recent centuries to contemporary literature, it aims to reveal different perspectives across space and time. Most appropriately, we start the series with an appreciation of Pausanias.

Rising on an outcrop overlooking the Aegean Sea, the sanctuary of Sounion is a stunning sight. Pausanias is, however, mistaken: the great Classical temple he saw is that dedicated to Poseidon.

On the Greek Mainland, facing the Cyclades Islands and the Aegean Sea, the Sounion Promontory stands out from the Attic land. When you have rounded the headland you see a harbour and a temple to Athena of Sounion on the peak of the promontory. (1.1.1)

Obviously, this quote is from a guidebook. Not any old guidebook, though, but the oldest cultural travel guide there is: those are the opening lines of the Description of Greece by Pausanias, written between the 150s and 170s AD. The Description (strictly speaking, the Greek title Hellados Periegesis translates along the lines of "guiding-around of Greece") is one of the most unusual works to survive from ancient literature, one of the most directly useful to Classical archaeologists active in mainland Greece - and one of the most fascinating for the discerning traveller. As Peter Sommer Travels' offerings now include tours of both Athens and the Peloponnese, Pausanias is of very direct relevance to us - so let's have a look at this exceptional book and its enigmatic author.

Much used in preparing our Athens and Peloponnese tour: Pausanias in the classic Greek-English edition.

Scope: The core regions of ancient Greece - and a lot of detail

But my text must not linger here, as I have all of Greece to describe. (1.26.4)

Having described an altar of Artemis on the Athenian Acropolis, Pausanias casually mentions his intended scope.

The Description of Greece consists of ten books, each of them concerned with a historical region of the Greek Mainland (namely 1. Athens and Attica, 2. Corinth, the Corinthia and the Argolid, 3. Sparta and Laconia, 4. Messenia, 5.-6. Olympia and Elis, 7. Achaia, 8. Arcadia, 9. Boeotia and 10. Phocis, Locris). Essentially, we are looking at the southern part of continental Greece, the Peloponnese peninsula and the region now know as Central Greece. As a chosen geographic area to cover, this makes fairly good sense, as it encompasses the area that is perceived as the heartlands of ancient Greek culture, the very region where Greek civilisation developed.

The structure of the books differs from region to region, perhaps reflecting their individual characters, or maybe due to changes in Pausanias' writing style over time. Broadly speaking, for each region he provides an introduction to its history, mythology, genealogy and geography before launching into his actual descriptions. Usually, these take us to the centre of the respective region's main city (or cities) and to its most important sanctuaries outside those, in each case describing the main sights to be seen at a place in a fairly systematic fashion. Outlying sites, smaller settlements and so on are normally treated more cursorily. As one would expect, the descriptions are frequently concerned with buildings, but they tend to treat the architecture itself in a surprisingly cavalier fashion, a frequent source of frustration for the modern archaeologist using Pausanias!

Nothing remains of the 12m (40ft) gold-and-ivory statue of Athena that stood within the Parthenon. Pausanias' description and Roman copies such as this one, on display in Athens, help us visualise this and many other lost treasures.

The statue of Athena stands upright, her garment reaching to her feet; on her chest is the head of Medusa, made of ivory. She holds a statue of Nike (...) and in the other hand a spear; at her feet is a shield and by the spear a snake. (1.14.7)

In contrast to that lack of architectural detail, Pausanias was clearly highly interested in art. His books abound in detailed accounts of the sculptures, paintings and other objects that adorned the sites he describes. Most of these works are now lost, making his work an extremely important source of information on a frequently missing aspect of ancient Greece.

Generally speaking, he pays more attention to the remains of the Archaic and Classical periods, many centuries before his time, than to those of the Hellenistic and Roman periods - which were relatively recent for him.

(...) here is a place called the plane tree grove, as a ring of tall plane trees is growing around it. This place, where the youths customarily fight, is like a sea island surrounded by a moat, and is entered by bridges. (...) Other rituals are performed by the youths, which I will describe now. Before the fighting (...) a group of youths sacrifices a puppy to Enyalos, believing that the bravest of domestic animals is a fit victim for the bravest of gods. No other Greeks to my knowledge habitually sacrifice puppies, except the people of Kolophon (...). At the sacrifice, the young men have trained wild boars fight one another (...). (3.14.8-9)

Pausanias reporting very specific ritual performances amongst the youths of Sparta, providing information that would be lost without his work and noting the very local character of what he describes.

Most importantly, Pausanias was driven by an informed fascination with historical and mythological narrative. His work shows a deep awareness of the very distinctive local variations that distinguished the Greek city-states in that regard, and moreover a fascination with the specific rituals and religious activities that arose from them - in other words, he focused strongly on local traditions. This is perhaps the most important contribution the Description of Greece makes to our understanding of ancient Greece. For a long time, Classical Studies tended to look at ancient Greece as a monolithic and consistent body, rather than recognising it as the diverse and dynamic phenomenon it really was. The fact that Greekness was a "broad church", that there were multiple ways to express and celebrate and live Greek identity within a very general framework of same language, same gods, comparable forms of state organisation and so on, is one that Pausanias not only recognised, but put at centre stage.

Remains of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, which housed the enormous gold-and-ivory statue of the god, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, that inspired Pausanias to give us an unsurpassed description as well as his own views on the nature of ivory...

Those who think that the things protruding from the mouth of an elephant are not the horns but the teeth of that creature should consider the elk, that animal of Celtic areas, and the Ethiopian bull. (...) An elephant's horns descend through the temples from above. (...) What I say is not hearsay: I once saw an elephant's skull at a sanctuary in Campania (Southern Italy)... (5.12.1-3)

A very short summary of Pausanias' digression - or diatribe - on whether ivory is horn or tooth, famously and pompously settling for what we now know to be the wrong answer. The section forms part of his immensely detailed description of another gold-and-ivory statue: that of Zeus at Olympia, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

A final significant aspect of the Description of Greece is Pausanias's habit of writing digressions. More often than not, he uses a place, building or object he describes to veer off into long-winded accounts of mythology, history or other detail, often seemingly unconnected to the item or place at issue. Now and then, he uses them to promote his own opinion, which is usually well-argued, but may still turn out wrong (as in our example above), a characteristic that Pausanias shares with Herodotus, the "Father of History", who was certainly an influence on his work and maybe his style. In fact, modern translations of the Description often omit those sections, an attempt to define and impose a view of when Pausanias is relevant and when he is not.

Pausanias who?

Pausanias is a tricky author for a number of reasons. Chief among them is his identity: who was Pausanias and why did he write? The persona, background and character of the man remain strangely elusive throughout the Description, reducing scholars to sifting for hints and engaging in speculation to various degrees.

Pausanias was evidently a man of learning. In his era, many cities had great libraries, like that donated by the Emperor Hadrian to the city of Athenss. Evidently, he frequented them.

Today, Thebes in Egypt and Orchomenos [in Arcadia] are less wealthy than a private man of moderate means (...). (8.23.2)

Thebes and Orchomenos both existed as - not particularly prosperous - towns in Pausanias' day. By comparing the wealth of an individual to that of a community (in his description of Arcadia), he identifies himself as a man of considerable wealth.

It is clear that Pausanias was Greek, well-educated and able to travel widely in Greece and beyond, including time to pursue his cultural interests, which implies that he must have enjoyed at least one important privilege: wealth. Most experts agree that he probably came from Asia Minor, most likely from Ionia or Lydia, i.e. the west or northwest of what is now continental Turkey. In that context, he would have been a Roman citizen of Greek language and background, able to describe Mainland Greece from the perspective of both a Greek and a foreigner.

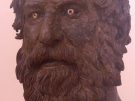

In Pausanias' day, Roman Emperors sported beards to look like Greek philosophers (and probably Pausanias did so himself). Their fascination with Greek culture had a long pedigree. Three centuries earlier, this portrait of a Greek philosopher was lost at Antikythera, along with the cargo of a ship carrying Greek art to Italy (National Museum, Athens).

He did so at a time when Greek men of learning were respected and appreciated in the Roman World. For centuries already, having travelled was considered a hallmark of experience, education, even wisdom. Upper-class Romans tended to spend a year or so of their youth studying in Greek centres of learning, such as Athens or Rhodes, and those who could afford it might travel to see the great historical and cultural sights of Greece and beyond - and local guides were available. In other words, the period knew an early form of tourism, providing Pausanias with a potential target audience.

I have listed the statues of of Zeus within the Altis (the inner sanctuary at Olympia) most accurately. (5.25.1)

Pausanias shows pride in his description of Olympia. He deserves it: his account is indeed astonishingly detailed and opens up a whole series of insights on that important and fascinating site that would otherwise not be available.

Pausanias' Greek is fine but not polished. He avoids rhetorical flourishes and tends to stick to a rather factual and descriptive account. His personality might shine through in the form of a slight insecurity, a need to validate his account: he often mentions the sources of his information, and frequently points out alternative or unusual versions of myth and religion. Further, he repeatedly stresses that his descriptions are based on personal inspection of the sites and cities and also that he has travelled further afield, including Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Italy and Rome herself.

No information about Pausanias exists in contemporary sources outside his own work, nor in subsequent centuries. The Description stands alone and isolated, unmentioned and perhaps unnoticed by other scholars and writers in antiquity. We're lucky that it has survived across eighteen centuries.

A unique source - and its peculiarities

Although some modern scholars dispute this, to me it appears clear that the Description was indeed written as a guidebook, as a handy source of information for the interested traveller. It is this that makes it unique within the body of ancient literature. By Pausanias' time, history was well established as a defined area of scholarship, its beginnings in the 5th century BC. Likewise, and for even longer, there was a highly developed field of geographical writings, concerned with mapping the world and directly useful e.g. to commercial travellers. There would, however, not be a defined genre of travel guide literature for more than a millennium and a half!

A headland called Minoa juts into the sea near the town [of Epidauros Limera]. The bay has nothing different to it than all the other sea inlets of Laconia, but the beach has pebbles of more attractive shape and of all colours. (3.13.11)

One of many incidental details in Pausanias. His "Minoa" is now better known as Monemvasia, the remarkably beautiful Byzantine and Venetian town set on a rocky promontory protruding into the Aegean.

Pausanias and his Description have received much criticism. He is accused of giving poor or ambiguous directions, of being selective in what he describes or of missing key aspects of his sites, of being biased in favour of certain cities, monuments, individuals or periods, of being inconsistent in style and being self-contradictory, and so on. The most common complaint is probably about his digressions interrupting the flow of descriptive narrative. It is also often lamented that the Description does not include various areas, such as Ionia, Crete, Macedon or the Aegean Islands.

One of the more baffling omissions in Pausanias: the 2nd century BC Stoa of Attalos is in the Agora of Athens. It is an enormous and visually dominant structure (reconstructed in the 1960s). Pausanias does not mention it at all.

Although it is hardly my place to defend a writer who lived over 1,800 years ago (others have done so in any case), two key points can be made here:

- We do not know the exact (or even general) conditions under which the Description was written: when and how often Pausanias travelled, how long afterwards he wrote up his books, whether he worked from notes, memory or both, where he did so, what his personal circumstances were and (again) so on. Since the Description - unusually - includes neither an introduction or even an introductory passage, nor a conclusion (it starts abruptly with the passage quoted at the start of this post and ends with a seemingly random anecdote), we have no direct statement of the author's intentions or the exact way he envisaged his work to be used. Therefore, any accusation that he did not fulfil his mission or aim is to be taken with more than a grain of salt.

- As someone who has been involved in editing a guidebook, I can make a more personal point. Imagine coming up with the idea of a cultural guidebook when no such thing existed and when maps and other such material were rare, travelling during an era when that was much harder than now, compiling and writing by hand or dictation, and dealing with immensely complex, convoluted and biased sources of information. Try to write a Baedeker on that basis! The truth is, of course, that even the best modern guidebooks are - necessarily - selective and probably often inconsistent: expecting perfection from a pioneer (by the best part of two millennia) is absurd. Moreover, Pausanias does not conceal the selective nature of his work:

To avoid misunderstandings, in my description of Attica I stated that I was not listing everything in order, but had chosen what is most noteworthy. I repeat the same before I write of Sparta. (3.11.1)

Travelling with Pausanias

The Description of Greece and Pausanias' effort in creating it are without any doubt of enormous and enduring value, especially when travelling in Greece, but also more generally to envisage life in antiquity. In this respect, there are three specific factors to stress, two to do with facts, the third with perspective.

The 6th century Temple of Hera at ancient Olympia. Pausanias gives us a detailed description of the building and the works of art it contained, but also of the female athletic contests held in honour of the goddess.

Every fourth year, a robe is woven for [the statue of] Hera (at Olympia) by the Sixteen Women; they also hold games called Heraia. This contest is made up of foot-races for maidens. (...) The first race is by the youngest, followed by those next in age, the oldest maidens run last. They run like this: hair hanging down, garment reaching down above the knee, the right shoulder bared down to the breast. (5.16.2)

- Pausanias adds dimensions that would otherwise be unattainable to our understanding of excavated archaeological sites in Greece. Where archaeology would normally be able to tell us "this is a temple, probably to such and such a deity, and probably from such and such a date", Pausanias is able to specify the god or goddess, their specific role, the local story of the monument, the beliefs attached to it and the rituals performed there. Where archaeology would tell us "this is a statue base", Pausanias might describe the now missing statue and explain who put it up and what event they commemorated. Thus, he adds immense depth, to what we can say about the sites he covers, e.g. at the Acropolis or Agora on Exploring Athens or at Olympia or Messene on Exploring the Peloponnese.

The finely preserved Ancient Messene in the Peloponnese. Pausanias' detailed account of its sculptural decoration, only part of which is preserved, provides deep insights into the ethnic, cultural, religious and political identity of the city.

- Pausanias frequently describes important objects, such as statues, paintings or furnishings, that have not survived. Since such objects were a key expression and factor of the respective site's or building's cultural meaning, as important as the architecture itself, his account is invaluable both in terms of fact and in triggering our imagination of what the places he describes were like.

- Throughout his Description, Pausanias prefers to tell a story that is not just about stones and buildings, but about the people who created them. From the mythological characters in the background via the historical personages that were connected with the sites to the beliefs and rituals attached to these places at his time, he adds a human element to what would otherwise be just rocks, conjectures and abstractions.

The 3,300 year-old Lion gate at the Bronze Age citadel of Mycenae was first described by Pausanias. His reference to the mythical giants is also the reason why such walls are described as "Cyclopean" to this day.

Parts of the city wall remain (at Mycenae), among them the gate, surmounted by lions. They say it is the work of the Cyclops (...). (2.16.5)

In short, Pausanias, while his work is sometimes entertaining, sometimes dull, sometimes confusing and sometimes highly insightful, is a huge and unique help in understanding the sites he describes. As he saw the cities and sanctuaries when they were still active, his account fills them with colour and life. Beyond that, he was a true pioneer, nearly two millennia ahead of his time.

You can read Pausanias' Description of Greece in print or online and you'll meet him again before long on these pages. But the best way to experience his work and its impact is to join us on our Exploring Athens tour or Exploring the Peloponnese tour, to see, hear and (that's up to you) read about the fascinating heritage of a land that fascinated him and fascinates us for being an immensely diverse wellspring of human achievement.

Leave a Reply