Aiani is not a well-known site, even among ancient historians. It’s in a region anciently called Elimia or Elimiotis, part of what’s known as Upper Macedonia. The latter isn’t just a geographical description of this highland region; it designates a part of what became the greater Macedonian kingdom that was to a considerable degree separate in its earlier history. Before I first came here, my expectations were primed by the little said about the area in Thucydides and other historians. There, it has a rather forbidding aspect: an upland place of rugged warriors, a problem, a threat. Macedonian kings struggled to keep it under control, and even the great Spartan general Brasidas had a heart-stopping moment of being abandoned by his allies in the midst of it and forced to undertake a nerve-destroying, tense retreat back to the sunlit, safer lowlands. Beyond terrifying episodes like that, we don’t get to hear much about the region. Enigmatic, unhelpful snippets – a line in Thucydides about a King Derdas here, a brief note about an Illyrian invasion there. Taken together, you’d assume it was a backward, rugged, inhospitable nest of terrifying skin-clad natives.

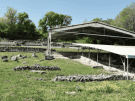

View of the 'royal' tombs at Aiani from the settlement.

Actually, coming to the place, and Aiani in particular, will make you feel like you’ve been duped – or at least not reading carefully, because it’s not like that at all. Sure, it’s hilly and parts are rugged, defensibly so, but any impression that this was a sunless place shut off from civilisation, destined only to step into the light of history to throw a spanner in its works, is wildly off.

The first clue to this comes on the drive. Polybius was absolutely right that a historian can only appreciate the subject under study by traversing the place. Driving into this part of Upper Macedonia from the plains around Thessaloniki and the core of the Macedonian realm is a real learning experience, and a hugely pleasant one, especially under a smiling sun and blue sky.

A marble lion from the burial cluster dated around 500 BC.

Firstly: it’s beautiful. It’s so much greener than you might expect, with broad expanses of level viridescent fields taking up a lot more of the view than the historians led you to expect: this is not poor country. The road is occasionally flanked by verdant eminences that, seemingly on a series of whims have decided to abruptly extrude themselves from the ground, while further away the more familiar olive-coloured hills speckled with vegetation sweep upwards. There is rough and difficult country to be had – there are grand alternate routes over a high ground filled with switchbacks, wind turbines, remote chapels and awesome views, thickly blanketed with trees which would have been difficult to traverse easily, but perhaps a great arena for the Macedonians’ love of hunting.

Aiani itself was probably spread over a number of the lesser eminences to the north of the river Haliakmon, a multi-noded settlement, where the most important bit may have shifted as time went on, but all probably counted towards the name. The archaeological core of the ‘urban’ site is the shaggy green hill of Megali Rachi, not far from the modern small town. It has a long history from the Neolithic right through to the end of the Hellenistic, but after that we lose sight of the built core. We have decent enough ideas where it may be, but for the Roman and early Byzantine period, it is burials that are the main tellers of tales about the inhabitants’ lives.

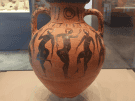

A Black Figure amphora with flute players and komasts.

Burials are pretty important earlier on, too. There are several different cemeteries dotted around the area and within a few kilometres of the main ‘nodes’ of Aiani. We have Neolithic and Bronze Age burials that have a characteristically different feel to those more familiar down south. There’s the typical matt-painted pottery of the north with great upthrust handles, like the pair of glasses on some grand dame subverted in a Far Side cartoon. As the latter period wears on we also have an influx of Mycenaean pottery – and even one sherd with Linear signs on it. This Mycenaean presence or contact – whichever this represents – is something that’s become ever more obvious in the last generation or so of work. Already, this was no backwater, but increasingly part of the Aegean world.

For my money, some of the nicest material is from the Iron Age burials, even if the material is mostly bronze – this is the jewellery (mostly, but the bronze also includes weaponry) that went into the interments. I’ve long been partial to this kind of stuff, whether from Luristan or the interior of Iron Age Europe. This material is particularly nice for its variety: long pronged pins, thick bangles whose incised decoration you have to move your head to catch the light of, now that the metal no longer has its original sheen, sinuous triangular fibulae, chunkily-knobbed pendants and the endless swirling ‘spectacle’ fibulae. Some of these strongly evoke material I’ve seen in the Celtic world, Sicily and Italy, the spectacle fibulae especially. Not dissimilar items were in the recent exhibition in Athens on the Italian Basilicata. As you look at these whirling dark green spirals, some partnered-up, almost like an antique kitchen hob, it feels like a different Greece, a path not exactly persisted with.

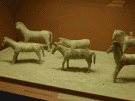

We can’t complain too much about that though. The later material is also gorgeous. Finely moulded silver pins, gold mouthpieces with repoussé decoration and a wonderful series of Archaic horses that almost feel like small-scale escapees from the world of the Terracotta Warriors.

A bronze collar, glass bead necklace, pins and spectacle fibulae.

Terracotta horses, part of the grave goods in a sixth century BC burial.

A fair bit of this material comes from the site of Leivadia on the lower ground near Megali Rachi, and it’s a key visit for us. Again, for those allowing prejudices to form from the historians, it’s a really unexpected site. It’s set amid a much wider burial ground, some of which had been used for centuries already. What marks it out is the way it was used in the late Archaic and Classical periods, the time when the Macedonian kingdom, and its Upper Macedonian semi-subordinates were forming. It certainly seems to reflect that history, with built stone tombs of ever greater size and complexity, culminating in the particularly impressive Tomb A, a good ten metres square with huge well-cut ashlar blocks, far from easy to shift into position. This and the other tombs have signs of at least some building above the ground surface, free-standing Doric and Ionic columns, guardian lions in the serene Archaic art style, funerary stelae and so on. Other structures seem to be for some sort of recurring religious commemoration or worship of the dead. As for the interiors, the stone lined pits for the burials, some of these were improved with bands of purple paint and on Tomb I, this band stands below something extra special. Here, on a now-lost wooden panel backing, were once pinned a series of cavorting animals, water birds, shield-bearing warriors in chariots and women, all of them from the hand of a skilled craftsman of the Archaic period, some two-and-a-half thousand years ago. The grave goods we’ve talked about already: gold mouth-covers and earrings, magnificent and huge silver pins and plenty of pottery (and its contents), some local, some from the wider Greek world. The whole assemblage feels like a parallel tradition, and a partial precursor to the great Macedonian burials of the fifth and fourth centuries BC. It’s difficult not to feel these are ‘royal’ and, even though we only have snippets of the region’s history, it’s not impossible that we know some of their names. At the very least, these are wealthy people, even if not kings.

Their burials would have been easily visible from the hill of Megali Rachi, the main known part of the settlement of ancient Aiani itself. This, too, gives the lie to the idea that Elimian Upper Macedonia was a benighted backwater. Granted, it’s nothing of the scale of Athens or the city-states of the islands and Asia Minor, but it’s an organised settlement, revolving round an open space bordered by stoas – colonnades, surely the ancient agora: Aiani’s marketplace and political centre. There’s a building with an impressive, deep and well-built public well above, and shops making and selling pottery. There are houses clambering up the hill’s sides, filled with domestic goods and little shrines, some with stairs running up their different levels. It all feels intimate and intricate, not unlike a lot of modern Greek villages, and you can almost hear the bustle of the busy denizens of the hill even today, above the fine views of the river off to the south. All this makes Aiani a great place to take stock of the achievement of Philip II in bringing these Upper Macedonian territories permanently under direct royal power. We can see these were organised, relatively sophisticated, agriculturally rich and well-defended territories, with a warrior ethos that had tripped-up more than one invader. They were no push-over, but once absorbed, Philip recognised the value of what he had. We can clearly see that in the reign of his son, Alexander the Great, the names of whose great generals very often called out their origins in the hill country of Upper Macedonia. They were a treasure of another sort.

To visit Aiani with one of our expert tour leaders, why not join one of our Exploring Macedonia tour.

Leave a Reply